Three months ago, I happily announced that the complete text of the November 1914 issue of Mother Earth had been made available at the Fair Use Repository. To-day, I’m pleased to follow up that announcement — with the announcement that the Fair Use Repository now features the complete text of three issues of Mother Earth. The two issues recently made available are:

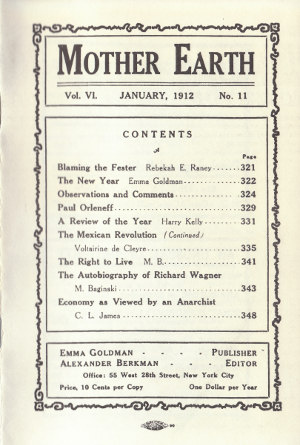

This issue is mainly occupied with the arts and revolution. It leads off with Blaming the Fester, a poem by Rebekah E. Raney. The New Year is a fundraising appeal on the occasion of Christmastime and the New Year, while Observation and Comments includes short reports on current events — delays in the publication of Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, the trial of the bosses who’d locked workers into the the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, strikes and conspiracy trials around the country, Big Bill Haywood’s feud with the Socialist Party of America, and more.

This issue is mainly occupied with the arts and revolution. It leads off with Blaming the Fester, a poem by Rebekah E. Raney. The New Year is a fundraising appeal on the occasion of Christmastime and the New Year, while Observation and Comments includes short reports on current events — delays in the publication of Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, the trial of the bosses who’d locked workers into the the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, strikes and conspiracy trials around the country, Big Bill Haywood’s feud with the Socialist Party of America, and more.

Paul Orleneff offers a celebratory review (unsigned, but probably written by Emma Goldman) of the actor’s performances in New York. A Review of the Year, by Harry Kelly, and the continuation of a serialized article by Voltairine de Cleyre on The Mexican Revolution, discuss revolutions and uprisings flaring up throughout the world in 1911. In The Right to Live M. B.

argues that political rights are empty without workers’ material control over the means of their own survival (the organization of society in a manner to insure to each the material basis of life and make it as self-evident as breathing

). Max Baginski reviews the Autobiography of Richard Wagner, taking it as evidence of the old commonplace that one can be a great artist and yet small as a man,

and concluding that The suffocating dependence of artistic production upon wealth and patronage should cause the true artist–who is not content to produce mere market ware–to turn relentlessly rebel against the existing standards, to become a communist. … The dream that Wagner once dreamed in Art and Revolution will some day be realized by the people,–nor will they need the aid of philosopher or king.

The issue concludes with a continuation of the serialized article Economy as Viewed by An Anarchist by C. L. James, on the historical emergence of the bourgeois system and its connections with past forms of economic hierarchy, as well as with the subjection of women.

The February 1913 issue has a few things to say about the State and a lot to say about the union struggle, Syndicalism, and government repression of striking workers. The issue leads off with To Our Friends, an appeal for readers to help widen the circulation of the journal, followed by another monthly instalment of short reports in Observations and Comments — including remarks on the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, the futility of appeals to the law, the advantages of direct action, new strike arbitration laws in New Zealand (among the first such labor laws in the world), the legal repression of Anarchists in the U.S., police scandals in Denver, and the incorporation of the Rockefeller fund.

The February 1913 issue has a few things to say about the State and a lot to say about the union struggle, Syndicalism, and government repression of striking workers. The issue leads off with To Our Friends, an appeal for readers to help widen the circulation of the journal, followed by another monthly instalment of short reports in Observations and Comments — including remarks on the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, the futility of appeals to the law, the advantages of direct action, new strike arbitration laws in New Zealand (among the first such labor laws in the world), the legal repression of Anarchists in the U.S., police scandals in Denver, and the incorporation of the Rockefeller fund.

James Montgomery’s The Black Hundreds of Plutocracy and Government discusses the use of private security forces, with tacit or explicit government approval, to inflict large-scale violence on striking workers. The New Idol, a translation of an excerpt from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, declares the State the coldest of all cold monsters.

Theodor Johnson’s Help Save These Comrades! reports on the case of a group of striking Swedish dock workers, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment for a bomb plot, and calls for international solidarity to get their sentences commuted. Making a Strike a Crime government’s assault on the rights to picket and speak freely, with the imprisonment of dozens of peaceful picketers and speakers in Little Falls, New York during a textile mill strike. Intolerance in the Union comments on growing regimentation and bureaucratic control within conservative trade unions and reprints a letter from a comrade discussing his objections to a corrupt bargain made by his union’s labor bosses, which resulted in his being persecuted by the labor bosses and expelled from the union. Syndicalism: Its Theory and Practice concludes a long article by Emma Goldman on state-free Syndicalist organizing, with a discussion of Syndicalism’s characteristic methods — Direct Action, Sabotage, and the General Strike. The issue concludes with Anarchist writer and teacher Bayard Boyesen’s review of Alexander Berkman’s Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, and with an announcement of dates for Emma Goldman’s lecture tour through the Midwest.

Onward

These issues complete a set of three reprinted issues of Mother Earth that I picked up from a table at the Bay Area Anarchist Bookfair. I’d very much like to make available more of Mother Earth’s print run online. A number of partial and complete issues — mostly earlier issues — are currently available from The Anarchy Archives, and a fair amount is available for browsing in Google Books. But I’d like to liberate the latter from the Google Books’s inaccurate automatic markup, often capricious behavior, and hypertext-unfriendly environment. And in any case, there are a lot of gaps to fill in. If you have any suggestions on issues to prioritize, or good lines on copies to be transcribed, please feel free to leave a comment here, or contact me with the details.

Read, cite, and enjoy!