Here’s some more on mass-media reception of Anarchism during the early 20th century: a strange little piece from the Sunday New York Times magazine from May 8, 1910, on Anarchist Sunday schools in New York, focusing on the Ferrer Sunday School taught by Alexander Berkman. The Sunday schools were part of the large network of schools, cultural spaces and other institutions organized by Anarchists in large cities like New York during the early 20th century. (Like most Anarchistic educational projects, the Sundays were closely associated with the Modern School Movement and the thought of Francisco Ferrer). Either of the writer of the article, or his editor, couldn’t quite seem to decide whether they wanted this story to be a straight interview of Berkman and a description of how the Sunday Schools were operated, or whether they wanted another cookie-cutter Anarchist-menace scare story.

SUNDAY SCHOOLS THAT TEACH CHILDREN ANARCHY

A Thousand Young Persons Are Being Trained in New York to Be Successors of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman.

So quietly has the anarchistic propaganda been carried on in New York that it will, without doubt, send a chill of arctic iciness down the spines of the many people who profess to stand in holy horror of the theory to learn through this article that to-day anarchistic Sunday schools are in session here just as are Sunday schools for bringing up the young to follow Methodism, Baptism, or any other form of faith or creed.

There are easily a thousand children in these schools, children who will, beyond peradventure, grow up to be Alexander Berkmanns and Emma Goldmans, with perhaps a Ferrer or a Tolstoy appearing. They range in age from 6 years to 16. During the week they go to the public schools and sing their own part in the grand chorus of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” recite the lessons offered by the system of education there, and hurry home to help their parents in the tenements, just as do other children; but on Sunday they loom up as a little body of humanity isolated from the present sociological system requiring strict obedience and reverence for authority. They are to be the propagandists of anarchy in America when Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkmann have passed away, and old Ben Tucker over on Sixth Avenue has joined the dust.

To those with radical natures or inclinations, and who have had opportunity to observe, the earnestness of the Anarchist in the expounding of his doctrine is well known, but to the great mass of intelligent humanity, smugly and snugly satisfied with their lot, the picture of an Anarchist Sunday school secured for readers of The Sunday Times will prove something of a revelation.

To begin with, there is no God in the Anarchist Sunday school, and the tablet miraculously handed to Moses, with its ten Thou Shalt Nots,

is no more in evidence there than is the latest revised code of the laws of the State of New York.

As the Anarchist preaches against the theory of submission to authority and law, the Sunday school teacher in the Anarchist class takes care that even with children he gives no impression that he himself is entitled to exert authority over them. If an Anarchist child does not agree with what teacher says he may arise in his little might of independence and say so. If he shows reasoning power in his expression of view he is a likely scholar, for it is the aim of the Anarchist to bring children up with absolute independence of the long-established restrictions on free thinking.

Occasionally rises a little one in one of these Sunday schools and asks with the directness and disregard of consequences peculiar to children:

How about God?

The teacher does not answer the question. He does not avoid it. He tells the children to figure out what reasons they have for believing that there is a God. The young minds attack the terrific question and fall back from it like baby moths that have winged swiftly against their first lampshade.

The largest of the Sunday schools is in Avenue A. It is called the Ferrer Sunday School, and was, until the killing of the Spanish philosopher, known as the Radical Sunday School. How the name was changed will prove a story that may stand out with striking novelty in the child life of New York to-day. It shall be told a little later in this article.

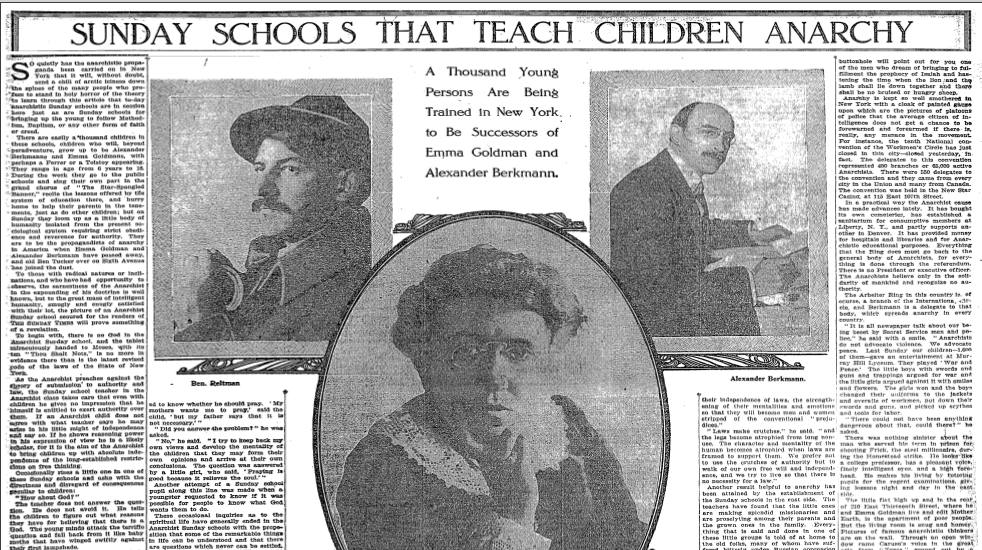

The Ferrer Sunday School is conducted by Alexander Berkmann. It has about eighty members and is in two classes. It meets on Sunday between 10 in the morning and noon. The youngest child is 7.

Berkmann has no laid-out system of teaching, depending on his comprehension of the psychology of the group at the time of the gathering. There are no rules. A song may be sung in chorus, a song dealing with freedom of mankind and hate for oppression. Some of the children may have learned by heart a poem or a fragment of an anarchistic argument and these provide recitations. The training of the mind anarchistically is then begun.

Berkmann, in a talk with a Times writer, in the office of Mother Earth, the Anarchist magazine, gave a sample of this teaching.

This was his talk to his Sunday school on Sabbath after the execution of Ferrer.

Once a single human being was swept from the sea to the shore of an island where there lived no human beings. There he found a great flock of sheep. He studied them and noticed that some of them were very powerfully built and finely fed. Some had even attained the strength and ferocity of wolves. But there were a great many of the sheep that were lean and worn. They were hungry and had been trampled down and hurt.

The man thought that he could so arrange it that these sheep, with little to eat and with bruises from being trampled, could be taught to care for themselves better and realize what the power of the strong and wolflike sheep had brought them to. He went among the sheep that suffered and began to point out to them what was the matter. The wolfish and strong ones heard of this and they turned upon the man and killed him.

When Berkmann finished this parable one of the children, a boy 18 years old, arose and said:

Why Mr. Berkmann, this story is just like the story of Ferrer’s death.

The children were so impressed with the parable and the discussion which followed that the name of the school was then changed from the Radical Sunday School to the Ferrer Sunday School.

In the classes,

said Berkmann, we generally use current events as subjects for discussion and study. For instance, one of our lessons was produced by the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York. The children of the east side saw a great deal of the sailors from the many men-of-war in the harbor. They saw the sailors of different nationalities entering and leaving the cafés, the best of friends, their arms about each other and acting like human brothers. The question naturally followed. Why should they be thus fond of each other and thus brotherly on land, and on sea be commanded to kill each other? They are brothers, and love each other, and there can be no fair reason for their slaying each other.

A man who had been raised in one of the old credal beliefs with care but who had come to be an agnostic in middle life once told the writer than when he realized that his religion had gone from him he felt that what he called reason had stepped into a nursery, and, like a willful bully, had gathered up the toys of a child sitting there and had destroyed them because he considered them useless. He considered the change from belief to agnosticism the tragedy of his life. The figure may be applied to thinking grown-ups easily, but it is hard to think of applying it to a child. And yet in the Anarchist Sunday school the tragedy of the destroyed toys is not infrequently enacted.

The pupil of the Anarchist Sunday school is taught to reason. The teacher only serves to direct their attention to a problem.

One child,

said Berkmann, wanted to know whether he should pray. My mothers wants me to pray,

said this child, but my father says that it is not necessary.

Did you answer the problem?

he was asked.

No,

he said. I try to keep back my own views and develop the mentality of the children that they may form their own opinions and arrive at their own conclusions. The question was answered by a little girl, who said, Praying is good because it relieves the soul.

Another attempt of a Sunday school pupil along this line was made when a youngster requested to know if it was possible for people to know what God wants them to do.

These occasional inquiries as to the spiritual life have generally ended in the Anarchist Sunday schools with the proposition that some of the remarkable things in life can be understood and that there are questions which never can be settled. The mental attitude of the children might be put in this way: We are not certain whether there are grounds for the belief that we should pray.

That, of course, leaves the question well in the field of agnosticism. The teacher of anarchy does not, with the children, declare that there is no God. Nor does he say that there is a God. The Sunday school class goes frequently to the Museum of Natural History, to Central Park, to the Zoological Gardens, and other places where, with the teacher, nature is studied.

The Ferrer Sunday school is only one of about fifteen similar schools in the greater city. Wherever the local groups of Anarchists can handle their own Sunday schools, carrying on the propaganda with literature, letters, lectures, &c., they do so without asking aid of others. When they cannot the State group helps. There is no central or superior group. Each has its own autonomy, although they all work to develop their principles of solidarity and mutual aid.

There are frequently conventions of the Sunday school teachers. Those who have classes get together and exchange experiences and ideas. In this city the Anarchists know that the fulfillment of their vision is afar, and they are already sowing their seed in the young and new fields that a generation of their kind may take hold of the propaganda when the present generation has withered and fallen.

These little Anarchists are being trained to believe in no authority. As Mr. Berkmann put it, everything is being done for them to aid them in the development of their independence of laws, the strengthening of their mentalities and emotions so that they will become men and women stripped of the conventional prejudices.

Laws make crutches,

he said, and the legs become atrophied from long non-use. The character and mentality of human becomes atrophied when laws are framed to support them. We prefer not to use the crutches of authority but to walk of our own free will and independence, and we try to live so that there is no necessity for a law.

Another result helpful to anarchy has been attained by the establishment of the Sunday schools in the east side. The teachers have found that the little ones are making splendid missionaries and are proselyting among their parents and the grown ones in the family. Everything that is said and done in one of these little groups is told of at home to the old folks, many of whom have suffered bitterly under Russian oppression and who have revolution deep in their hearts. They write letters to the Anarchist teachers and get replies. They discuss the views expounded at home by their children and many of them become radicals and join the Anarchist groups.

The Anarchists also spread their propaganda by establishing little libraries which they make easily accessible to all who want to study the theory.

In the spreading of the propaganda among the children the littlest are not overlooked. There are some as young as six years of age who are getting kindergarten lessons in anarchy. One of these lessons is the lesson which preaches to a boy of health and strength at the age of six that he should not strike or abuse a boy who is not as strong as he is but should help him because he needs help. That is the very heart of the kindergarten lesson.

All of this work is done in what is called the Workmen’s Circle. The Circle is the general group and is known as the Arbeiter Ring. A little white enamel badge with the letters A. R.

in the buttonhole will point out for you one of the men who dream of bringing to fulfillment the prophecy of Isaiah and hastening the time when the lion and the lamb shall lie down together and there shall be no bruised or hungry sheep.

Anarchy is kept so well smothered in New York with a cloak of painted gauze upon which are the pictures of platoons of police that the average citizen of intelligence does not get a chance to be forewarned and forearmed if there is, really, any menace in the movement. For instance, the tenth National convention of the Workmen’s Circle has just closed in this city–closed yesterday, in fact. The delegates to this convention represented 450 branches or 65,000 active Anarchists. There were 550 delegates to the convention and they came from every city in the Union and many from Canada. The convention was held in the New Star Casino, at 115 East 107th Street.

In a practical way the Anarchist cause has made advances lately. It has bought its own cemetaries, has established a sanitarium for consumptive members at Liberty, N. Y., and partly supports another in Denver. It has provided money for hospitals and libraries for Anarchistic educational purposes. Everything that the Ring does must go back to the general body of Anarchists, for everything is done through the referendum. There is no President or executive officer. The Anarchists believe only in the solidarity of mankind and recognize no authority.

The Arbeiter Ring in this country is, of course, a branch of the International Circle, and Berkmann is a delegate to that body, which spreads anarchy in every country.

It is all newspaper talk about our being beset by Secret Service men and police,

he said with a smile. Anarchists do not advocate violence. We advocate peace. Last Sunday our children–1,000 of them–gave an entertainment at Murray Hill Lyceum. They played War and Peace.

The little boys with swords and guns and trappings argued for war and the little girls argued against it with smiles and flowers. The girls won and the boys changed their uniforms to the jackets and overalls of workmen, put down their swords and guns, and picked up scythes and tools for labor.

There could not have been anything dangerous about that, could there?

he asked.

There was nothing sinister about the man who served his term in prison for shooting Frick, the steel millionaire, during the Homestead strike. He looks like a college professor, has a pleasant voice, finely intelligent eyes, and a high forehead. He makes his living by tutoring pupils for the regent examinations, giving lessons night and day in the east side.

The little flat high up and in the rear of 210 East Thirteenth Street, where he and Emma Goldman live and edit Mother Earth, is the apartment of poor people. But the living room is snug and homey. Pictures of famous anarchistic thinkers are on the wall. Through an open window came Caruso’s voice in the great aria from Tosca,

ground out by a phonograph, as Berkmann talked with the Times man. It was a warm combination, but the night was warm, and we were glad for the breeze that swept the little place however burdened it might be.

We teach no ism,

he said, harking back to the Sunday schools. Our aim is to develop character and mentality in the child. We try to make them think, criticise, and feel.

We want their emotional and intellectual natures developed. We want to make them men and women absolutely free of the old restrictions. We hope that they will grow up with the spirit of solidarity and co-operation in them. We try to teach them that in and out of school.

We try to teach them ethical right and reason. Our Radical Boys’ Literary Club, boys about 13 or 14 years old, hold meetings after school, and they run their organization just as the grown people do. They have advanced to where they need no help from their elders.

Among the grown Anarchists the cause is kept warm by fervid preachings in their publications. These are the weekly paper Frei Arbiter Stimme, with a circulation of 12,000; Mother Earth, with a circulation of 6,000; Freiheit, with 5,000 circulation, and Voine Listy, a Bohemian paper, with a circulation of 4,500.

There are nine large groups of the grown Anarchists in New York. These have regular meetings, and conduct the propaganda with lectures, debates, &c.

In the district from Fourteenth Street to the Battery east of Broadway are 850,000 people living. Here beats the heart of anarchy. Nearly all of these people are foreign born, the native born element being insignificant in its percentage.

Forsyth Street, Chrystie, Cannon, Pitt, Columbia, Second Streets all have buildings in which are tiny halls that may be rented for a dollar or two for a wedding, a banquet, a lodge meeting, or a group meeting of Anarchists.

The man who lives awhile in this teeming corner of Manhattan does not take long to find out where he can go and hear all the anarchy he wants expounded. The writer once met in one of these little halls S. Yanofsky, the editor of the Frei Arbiter Stimme. A man with dreamy eyes, pointed beard, and nervous energy, he seemed to be looked up to as little short of a god by a clump of young men and women who were wating for him.

Yanofsky and Berkmann were both rounded up by the police after the Silverstein bomb explosion in Union Square in 1908, and as there was nothing against either of them nothing came of the call to Police Headquarters. Yanofsky, when asked by the writer what he thought of Silverstein’s act, replied:

The man who commits a violent deed, if he is not mad, is desperate. Violence never did any good for anarchy. All government is a form of violence. Suppose Silverstein had suffered personally–and his act was that of an impatient and ignorant man–what did he accomplish? He only made himself dead and gave the chance to the enemies of anarchy to spread their calumnies. He only helped them to kill of the chances of gaining liberty.

Berkmann was a little clearer on the matter of violence and anarchy.

If a Republican or Democrat should throw a bomb or kill another,

he said, the Republican Party or the Democratic Party would not be blamed for it. When an Anarchist does a thing like that we frankly say that anarchy did not inspire it, but that conditions of inequality and injustice caused the crime. To stop the crime, stop the cause. Anarchy is for justice and freedom. It cannot be blamed for individual acts of violence.

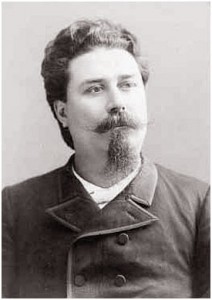

Among the favorite east side speakers for anarchy, besides Yanofsky and Berkmann, is Dr. Ben Reitman, whose method is to stir up the hearers with fiery sentences depicting the wrongs resulting from the present order of things. He with the others believes that anarchy is gathering strength, and will continue to gather it and will prove a living force in the slow movement of society through the ages.