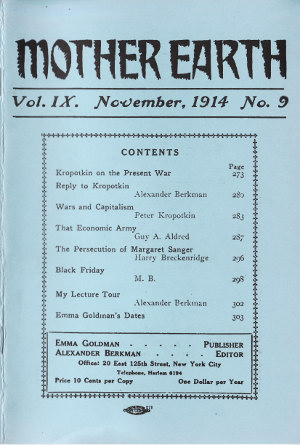

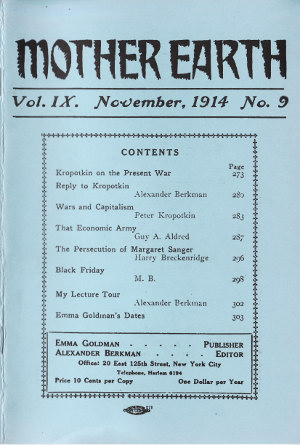

I’m happy to follow up our earlier announcement with an announcement that the Fair Use Repository now features the complete text of all the articles from the November 1914 issue of Mother Earth.

Most of the issue is occupied with Anarchist responses to, and debate over, the outbreak of World War I: Kropotkin on the Present War reprints Peter Kropotkin’s letter to Gustav Steffen, supporting the French government’s fighting in World War I; Alexander Berkman’s In Reply to Kropotkin calls Kropotkin to task and argues that Anarchists should oppose all sides in all government wars. Goldman and Berkman followed this argument with a reprint of Chapter I of Kropotkin’s own Wars and Capitalism, written in 1913, in which Kropotkin had skewered the French government’s motives and argued that wars were the product of imperial capitalism and that the reason for modern war is always the competition for markets and the right to exploit nations backward in industry.

In addition to the exchange over Kropotkin’s letter, this issue also features That Economic Army, an article by Guy A. Aldred originally printed in the London Spur, which traces how the state and capital, during wartime, deformed the entire economy to draw not only men, but entire industries, into collaboration with the war machine, out of economic interest.

Alongside the discussion of the war, Vol. IX. No. 9 also features:

The Persecution of Margaret Sanger by Harry Breckenridge, a defense and a call for working-class solidarity with Margaret Sanger and the Woman Rebel, then facing Federal prosecution for obscenity

(for distributing articles on birth control and scientific information about sexual health).

Black Friday of 1887 by M. B.,

a slashing review of the Socialist journalist Charles Edward Russell’s discussion of Haymarket in his memoirs, and a commemoration of the Haymarket martyrs hanged 11 November 1887.

My Lecture Tour by Alexander Berkman, an announcement of Berkman’s upcoming lecture tour of the Midwest, with talks on War–At Home and Abroad,

Unemployment and War,

War and Culture,

The War of the Classes,

Is Labor Justified in Using Violence?

Crime–In and Out of Prison,

and The Psychology of Crime and Prisons.

Emma Goldman Dates by Emma Goldman, an announcement of Emma Goldman’s upcoming lectures in Chicago on anti-militarism, Anarchism, and a lecture series on drama , as well as announcing dates for upcoming lecture series elsewhere in the Midwest.

I’m happy to have this issue of Mother Earth available in full. More issues should be coming soon.

Read, cite, and enjoy!

posted 11:15 pm by Rad Geek | 1 comment

Now available thanks to Shawn P. Wilbur at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth:

[Part 1] - [Part 2] - [Part 3]

XIX

With governmental control, such as was held by fallen administrations and such as we have preserved until the current time, one can boldly address a challenge to any who would seriously accept public functions; that would be to diminish the personnel of two formidable armies that weigh at the same time on the liberties and on the fortune of France: the army of the offices and that of the barracks. One can challenge him, consequently, not to proclaim liberty—if that happens I will laugh—but to introduce that liberty into actions and lead him to be something other than a nonentity.

Even more, one could challenge him to reduce taxes. Better still! he is forbidden to keep them at sixteen million, a monstrous figure, of which, what is more, the insufficiency could easily be shown by whoever is finance minister.

Here, in its true colors, is what governmental control accomplishes: slavery and ruin.

That control, on attributing itself the right to rule according to its fancy the movement and the thought of each citizen, has produced, in the moral order, a result not less deplorable. Truly! it has legalized everything.

Oh well! one would be strangely mistaken if one believed that legality carries within its litigious bowels the seed of human probity.

The legislation of France is not founded on the respect of individuals; it is founded on the principle of violation of public right, since lese-majesty, respect for the king, for the emperor, for the government, is consecrated at its root.

The law has never had social sanction among us: there has only been royal sanction and sanction by governmental supremacy whose character has always been to protect the minorities.

Our legislation is therefore immoral, because it is not based on the majority.

This legislation, moreover, necessarily coming after the vices that it seeks to suppress, is in reality nothing but the consecration of these vices. A code teaching me what I must avoid and what I must do; and in its spirit I practice right conveniently enough, since I abstain from wrong. Well, this could introduce a fundamental deception in public belief, since an able man, confronted with the law, finds himself with the same features as a man who is truly virtuous.

A legally honest man is one against whom no grounds for complaint have been proven; but a skilful man is not without the right to claim the benefits of the same definition! He who has carried out shadowy misdeeds, without witness and without coming to grief, skillfully avoiding the prohibitive letter of the law, and who enjoys the protection of the judge is also a man against whom no grounds for complaint have been proven. This one, too, is an honest man! and he would be in greater error to follow the law of social equity, the rule of morality, while the legal gospel is there before his eyes, while he has a clear field in unforeseen circumstances, while he is, with his ability, up to all foreseen cases, and for whom, ultimately, there is the friendship of the judge.

According to legality, therefore, equity goes according to the judgment of the court and the public conscience is taken over by the conscience of statute book.

Legality! but in pushing the social body of the people into pure and simple legality, governments have created and brought into the world a fraud, the poetry of pugilism.

The man, required to have the skill to avoid the trap set by the legislator, does not even bother to become a hypocrite. After having cleverly escaped the forethought of the law, he boasts of it as something to recommend to his contemporaries; he has sailed close to the wind with the law and the victory is his: what a superior being!

It goes without saying that our legislation, made up of scholarly compendiums, whose scrutiny and interpretation is only for the erudite, has fallen short of the morality of simple people who have always been and do not cease to be the quarry of the jurists.

Here, then, is what the much vaunted work of the legislative assemblies have provided us with: a celebrated statute book, a gravestone raised by public grief on the tomb of virtue! Each moral failing has, on passing, come to write its formula on this glossy book, and, the more numerous the formulas, the more beautiful the statute book, but also the more beautiful the statute book, the more perverted the society.

XX

Something one should never tire of repeating, is that morality can only exist among free people, and free people are those whose government, speaking very little of the national language, speak above all foreign languages; the government of democracies is principally diplomatistic.

Among us, he who speaks of government speaks of the Republic, the State, society. These words, in effect, the red Republic, the tricolor Republic, etc., which try our patience, signify nothing but the red government, the tricolor government, etc. As far as the administration is concerned, the government, that is the Republic.

Who thinks this is wrong?

The men of today, indeed quite different from those of times gone by, sense, though they understand nothing, that their being and their property are entirely separate from the administrative body. They feel it so much that, on letting, as a result to custom, a government establish itself on a model of past times, they effectively retire from it, not granting it their confidence, and not agreeing to aid it materially, without grumbling, faced with force or in fear. They feel it so much so that they take it upon themselves to control, publicly, the acts of administration. Well, a power whose acts are controlled has forfeited its rights, since its authority is undermined.

But this error, which consists of hiding the whole of society under the symbol of government, is strongly embedded in public beliefs.

The influence of tradition has made of it an article of national faith, which everyday finds itself in more direct opposition with the public will and public sentiment.

Thus, everyone knows that a popular movement puts nothing in danger but the official fortune of a few men; despite public bills and proclamations saying that the movement puts society in danger, the nation allows it without further consideration.

If I wanted to adopt the reasoning of skilled people, who use for their own interests the powers that society confers upon them, this would lead me to a curious conclusion, a disappointing commentary on the tumultuous spectacle of revolutions!

XXI

I have seen, in the few years that my memory is able to embrace, a very respectable number of popular movements.

When these movements fail at the first step, their leaders are arrested, thrown into jail, tried and convicted as criminals of the State. The proclamations posted on every wall in Paris and sent to the very smallest township tell society that it has just been saved.

Certainly, at this news, logically I would have to think that if, by some sort of misunderstanding, authority had been overwhelmed, if the army had weakened, if the movement had gone beyond the law, that would have been the end of society: France would have been pillaged, sacked, set ablaze, lost!

When, however, these movements, mastering all obstacles, overturning authority, passing the armed forces have followed their course and arrived at their goal, then their leaders are carried in triumph, hailed as heroes and raised to the highest heights of the judiciary. The proclamations posted on every wall in Paris and sent to the very smallest township tell society that it has just been saved. Thus society, incessantly in danger, is always saved!

Who saves it? Those that put it in danger.

Who puts it in danger? Those that save it.

It is to say that society is never more completely lost than when it is saved.

And that it is never better saved than when it is lost.

And I said that by adopting the reasoning of the skilled people who make use of the power with which society endows them for their own personal ends, it would lead me to a curious conclusion!

Curious, indeed, and logically explicable by the facts.

Thus, taking us back to 23 February, according to the Journal des débat, Le Constitutionnel, Le Siècle and all the other newspapers that defend social order, it is understood that the agitators in Paris at that time were nothing but unsanctioned troublemakers who wanted nothing less than the subversion, the overturn and the ruin of society.

These unsanctioned troublemakers triumphed the next day and, immediately, every citizen said what he liked, wrote, printed what he liked, did what he liked, went where he liked, went out and came in when he liked; enjoyed, in a word, his natural liberty in all ways socially possible, amid the most complete security, favored by the most fraternal urbanity. Society was, in short, saved by and for each of its members.

Well, this happened the day when, according to the friends of order, society was lost.

Thus, again, to the voice of the defenders of social order became added, for reasons known to itself, that of Le National: the June agitators were nothing but unsanctioned troublemakers who wanted nothing less than the subversion, the overturn and the ruin of society. These troublemakers failed and, immediately, every citizen was barracked in his own home, scrupulously examined on his own premises, disarmed, thrown in jail by a simple ill-willed denunciation, reduced to the most complete and absolute silence, placed under the unruly surveillance of the state-of-siege police and governed by the sharp, pointed and undiscerning law of the sword. Society was, therefore, lost by and for each of its members.

Well, this happened the day when, according to the friends of order, this time including Le National, society was saved.

From which I am forced to conclude, just as I have already said and proven, that society is never more completely lost than when it is saved and that it is never better saved than when it is lost.

This is, oh France, the spectacle, as delicate as it is subtle, that plays out in front of other nations and before posterity, in the country the most intelligent in the world.

What an indecorous comedy!

XXII

I do nothing more here than to state the facts; I note them and report them as they appear to me. Regarding the commentary, I simply repeat what I have said elsewhere: I do not believe at all in the efficacy of armed rebellion, and for a simple reason, which is that I do not believe at all in the efficacy of armed governments.

An armed government is a brutal entity, since its only principle is force. An armed revolution is a brutal thing, because it has no other principle than force.

When one is ruled by the arbitrariness of barbarism, it is necessary to kick like a barbarian; and, as for the arms one crosses over their chests, the parties would do well to oppose weapons.

As much as a government, in place of improving the condition of things, only improves the condition of a few people, a revolution, the inevitable end of such a government, will only be a substitution of persons instead of being a change of matters.

Armed governments are the authorities of the movement, the administration of the party.

Armed revolutions are the wars of the movement, the campaigns of the party.

The nation is as much a stranger to armed government as it is to armed revolution; but if it is the case that a revolutionary party is more immediately worried than the nation by the governing party, it will also be the case that one day the nation worried in its turn will complain about the government, and that it will be in that precise moment that it will win the moral support of the people, that the revolutionary party will wage battle.

From there, this kind of public recognition leads to bloody rabble-rousing, which under the pompous title of revolutions, hides the impertinence of a few valets rushing to become masters.

When the people have understood the position that has been reserved for them in these Saturnalias they pay for, when they have realized the ignoble and stupid role that they have been made to play, they will know that armed revolution is a heresy from the point of view of principles; they will know that violence is antipodal to right; and once resolved on the morality and the inclinations of the violent parties, whether those of government or revolutionary, there will be a revolution among them brought about by the single force of right: the force of inertia, the denial of assistance. In the denial of assistance will be the repeal of the laws on legal assassination and the proclamation of equity.

This supreme act of national sovereignty I see happen here, not as a calculated result, but as an expression of the law of necessity, as an inevitable product of an administrative avidity, of the extinction of credit and the gloomy arrival of destitution. This revolution, which will be French and not solely Parisian, will tear France from Paris to lead it back to a municipality; then, and only then, will the national sovereignty become fact, since it will be founded on the sovereignty of the commune.

To these words of sovereignty of the commune, all the great minds, who have dragged patriotism to the bar of vocabulary to make the Republic a question of words, exclaim in admiration the name three times holy of unity.

Unity! The time is ripe speak about it. In the midst of the divisions tearing the country apart, I ask what has been made of national unity by the lame paraders who speak in its name!

Unity! I know of only one way to destroy it; that is to want to constitute it by force. If someone had the power to act on the planets, and if, under the pretext of constituting the unity of the solar system, he tried to make them adhere by force to the center, he would destroy the equilibrium and reestablish chaos.

There is someone here who supports unity more than anyone else; that someone is the French people; and if France does not understand that she must promptly leave the stomach of the administration, or else be dissolved there, that will not be my fault, nor the fault of the coarse peritoneum which elaborate the digestion.

XXIII

Let us say, moreover, that the result of an armed revolution, supposing that the revolution is generously interpreted by a kindhearted man, all-powerful over opinion, honest, disinterested and democratic like Washington, the result of an armed revolution, I have said, can turn to the profit of public law.

The tyrants overturned, before others come to take their place, there always appears, on top of the ruins of the tyranny, a man greater than the others, a man whom everyone sees, whom everyone hears, and he is the master of the debris; it is up to him to scatter it or reconstruct it.

If Monsieur de Lamartine had had the genius of action, as he had genius of matters of intelligence, 24 February would have been the date of the French Republic, instead of being nothing but invective.

France, on that day, had expected everything from that man, to whom national sympathies had spontaneously handed over the puissant steering of the destiny of the people.

He only had to say to us in the harmonious rhythm of his beautiful language: “The government of the king is abolished: France is no longer at the Hôtel de Ville!â€

“Your masters have gone and they will not be replaced!â€

“Their law was in force; it is in force no longer. It will not return!â€

“You are returned to yourselves; the foreigner will learn from me that you are free.â€

“Keep a watch over yourselves; I’ll keep a watch on the borders!â€

Certainly, after declarations so substantial, our representatives, whoever they had been, would not have lost sight of the fact that they had to define national law, and not the frenzied law of governments.

Perhaps Monsieur de Lamartine would have perished, a victim of ambitious men left without prey. The despair of the apprentice tyrants might perhaps have been unleashed on him; but his death, like that of all great citizens, would have been fecund! And since, as he said, ideas vegetate in human blood, his would have remained at the beginning of the free era, as an eternal protestation against the tyranny of the delivered.

Unfortunately, instead of scattering the elements of despotism, he set about collecting them together again in order to reassemble them; today the building is complete except for the keystone. It is not he that lives in it, but it is inhabited; not too much worse, perhaps, but not much better either.

Ah, well! the time has come to leave words and come to action!

The time has come to know what democracy wants to say!

The time has arrived for all Frenchmen, in whose arteries still beats a little Gallic blood, who, from Diocletian to Charlemagne, protested against the tyranny of the empire, to assume their position as free citizens, and to call to account the cowardice and the inability of the men of the people, the Republican individualities, for our collapsed credit, for our vanished capital, for our paralyzed industries, for our lay-offs, for our extinguished trade, for our products without market; for our France, finally, so unproductive, so alienated, so venal, so prostituted, so debased, so inhospitable, so foreign to ourselves, so polluted by the tax authorities, and so close to contempt for its children, that they will soon not have enough love in their hearts to set their courage against attempts by their ravishers!

The time has come, for we are facing a decisive spectacle: on one side there is the government which defies the nation;

On the other side, there is the nation which defies the government.

Well, it must be, by complete necessity, that either the government devours the country or that the country absorbs the government.

END

[Translation by Collective Reason (Robert Tucker, Jesse Cohn, and Shawn P. Wilbur.) Robert did most of the hard work, and I'm responsible for the final choices.]

Read the whole thing at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth.

posted 10:41 pm at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth | no comments

Now available thanks to Shawn P. Wilbur at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth:

[Part 1] - [Part 2] - [Part 3]

XIX

With governmental control, such as was held by fallen administrations and such as we have preserved until the current time, one can boldly address a challenge to any who would seriously accept public functions; that would be to diminish the personnel of two formidable armies that weigh at the same time on the liberties and on the fortune of France: the army of the offices and that of the barracks. One can challenge him, consequently, not to proclaim liberty—if that happens I will laugh—but to introduce that liberty into actions and lead him to be something other than a nonentity.

Even more, one could challenge him to reduce taxes. Better still! he is forbidden to keep them at sixteen million, a monstrous figure, of which, what is more, the insufficiency could easily be shown by whoever is finance minister.

Here, in its true colors, is what governmental control accomplishes: slavery and ruin.

That control, on attributing itself the right to rule according to its fancy the movement and the thought of each citizen, has produced, in the moral order, a result not less deplorable. Truly! it has legalized everything.

Oh well! one would be strangely mistaken if one believed that legality carries within its litigious bowels the seed of human probity.

The legislation of France is not founded on the respect of individuals; it is founded on the principle of violation of public right, since lese-majesty, respect for the king, for the emperor, for the government, is consecrated at its root.

The law has never had social sanction among us: there has only been royal sanction and sanction by governmental supremacy whose character has always been to protect the minorities.

Our legislation is therefore immoral, because it is not based on the majority.

This legislation, moreover, necessarily coming after the vices that it seeks to suppress, is in reality nothing but the consecration of these vices. A code teaching me what I must avoid and what I must do; and in its spirit I practice right conveniently enough, since I abstain from wrong. Well, this could introduce a fundamental deception in public belief, since an able man, confronted with the law, finds himself with the same features as a man who is truly virtuous.

A legally honest man is one against whom no grounds for complaint have been proven; but a skilful man is not without the right to claim the benefits of the same definition! He who has carried out shadowy misdeeds, without witness and without coming to grief, skillfully avoiding the prohibitive letter of the law, and who enjoys the protection of the judge is also a man against whom no grounds for complaint have been proven. This one, too, is an honest man! and he would be in greater error to follow the law of social equity, the rule of morality, while the legal gospel is there before his eyes, while he has a clear field in unforeseen circumstances, while he is, with his ability, up to all foreseen cases, and for whom, ultimately, there is the friendship of the judge.

According to legality, therefore, equity goes according to the judgment of the court and the public conscience is taken over by the conscience of statute book.

Legality! but in pushing the social body of the people into pure and simple legality, governments have created and brought into the world a fraud, the poetry of pugilism.

The man, required to have the skill to avoid the trap set by the legislator, does not even bother to become a hypocrite. After having cleverly escaped the forethought of the law, he boasts of it as something to recommend to his contemporaries; he has sailed close to the wind with the law and the victory is his: what a superior being!

It goes without saying that our legislation, made up of scholarly compendiums, whose scrutiny and interpretation is only for the erudite, has fallen short of the morality of simple people who have always been and do not cease to be the quarry of the jurists.

Here, then, is what the much vaunted work of the legislative assemblies have provided us with: a celebrated statute book, a gravestone raised by public grief on the tomb of virtue! Each moral failing has, on passing, come to write its formula on this glossy book, and, the more numerous the formulas, the more beautiful the statute book, but also the more beautiful the statute book, the more perverted the society.

XX

Something one should never tire of repeating, is that morality can only exist among free people, and free people are those whose government, speaking very little of the national language, speak above all foreign languages; the government of democracies is principally diplomatistic.

Among us, he who speaks of government speaks of the Republic, the State, society. These words, in effect, the red Republic, the tricolor Republic, etc., which try our patience, signify nothing but the red government, the tricolor government, etc. As far as the administration is concerned, the government, that is the Republic.

Who thinks this is wrong?

The men of today, indeed quite different from those of times gone by, sense, though they understand nothing, that their being and their property are entirely separate from the administrative body. They feel it so much that, on letting, as a result to custom, a government establish itself on a model of past times, they effectively retire from it, not granting it their confidence, and not agreeing to aid it materially, without grumbling, faced with force or in fear. They feel it so much so that they take it upon themselves to control, publicly, the acts of administration. Well, a power whose acts are controlled has forfeited its rights, since its authority is undermined.

But this error, which consists of hiding the whole of society under the symbol of government, is strongly embedded in public beliefs.

The influence of tradition has made of it an article of national faith, which everyday finds itself in more direct opposition with the public will and public sentiment.

Thus, everyone knows that a popular movement puts nothing in danger but the official fortune of a few men; despite public bills and proclamations saying that the movement puts society in danger, the nation allows it without further consideration.

If I wanted to adopt the reasoning of skilled people, who use for their own interests the powers that society confers upon them, this would lead me to a curious conclusion, a disappointing commentary on the tumultuous spectacle of revolutions!

XXI

I have seen, in the few years that my memory is able to embrace, a very respectable number of popular movements.

When these movements fail at the first step, their leaders are arrested, thrown into jail, tried and convicted as criminals of the State. The proclamations posted on every wall in Paris and sent to the very smallest township tell society that it has just been saved.

Certainly, at this news, logically I would have to think that if, by some sort of misunderstanding, authority had been overwhelmed, if the army had weakened, if the movement had gone beyond the law, that would have been the end of society: France would have been pillaged, sacked, set ablaze, lost!

When, however, these movements, mastering all obstacles, overturning authority, passing the armed forces have followed their course and arrived at their goal, then their leaders are carried in triumph, hailed as heroes and raised to the highest heights of the judiciary. The proclamations posted on every wall in Paris and sent to the very smallest township tell society that it has just been saved. Thus society, incessantly in danger, is always saved!

Who saves it? Those that put it in danger.

Who puts it in danger? Those that save it.

It is to say that society is never more completely lost than when it is saved.

And that it is never better saved than when it is lost.

And I said that by adopting the reasoning of the skilled people who make use of the power with which society endows them for their own personal ends, it would lead me to a curious conclusion!

Curious, indeed, and logically explicable by the facts.

Thus, taking us back to 23 February, according to the Journal des débat, Le Constitutionnel, Le Siècle and all the other newspapers that defend social order, it is understood that the agitators in Paris at that time were nothing but unsanctioned troublemakers who wanted nothing less than the subversion, the overturn and the ruin of society.

These unsanctioned troublemakers triumphed the next day and, immediately, every citizen said what he liked, wrote, printed what he liked, did what he liked, went where he liked, went out and came in when he liked; enjoyed, in a word, his natural liberty in all ways socially possible, amid the most complete security, favored by the most fraternal urbanity. Society was, in short, saved by and for each of its members.

Well, this happened the day when, according to the friends of order, society was lost.

Thus, again, to the voice of the defenders of social order became added, for reasons known to itself, that of Le National: the June agitators were nothing but unsanctioned troublemakers who wanted nothing less than the subversion, the overturn and the ruin of society. These troublemakers failed and, immediately, every citizen was barracked in his own home, scrupulously examined on his own premises, disarmed, thrown in jail by a simple ill-willed denunciation, reduced to the most complete and absolute silence, placed under the unruly surveillance of the state-of-siege police and governed by the sharp, pointed and undiscerning law of the sword. Society was, therefore, lost by and for each of its members.

Well, this happened the day when, according to the friends of order, this time including Le National, society was saved.

From which I am forced to conclude, just as I have already said and proven, that society is never more completely lost than when it is saved and that it is never better saved than when it is lost.

This is, oh France, the spectacle, as delicate as it is subtle, that plays out in front of other nations and before posterity, in the country the most intelligent in the world.

What an indecorous comedy!

XXII

I do nothing more here than to state the facts; I note them and report them as they appear to me. Regarding the commentary, I simply repeat what I have said elsewhere: I do not believe at all in the efficacy of armed rebellion, and for a simple reason, which is that I do not believe at all in the efficacy of armed governments.

An armed government is a brutal entity, since its only principle is force. An armed revolution is a brutal thing, because it has no other principle than force.

When one is ruled by the arbitrariness of barbarism, it is necessary to kick like a barbarian; and, as for the arms one crosses over their chests, the parties would do well to oppose weapons.

As much as a government, in place of improving the condition of things, only improves the condition of a few people, a revolution, the inevitable end of such a government, will only be a substitution of persons instead of being a change of matters.

Armed governments are the authorities of the movement, the administration of the party.

Armed revolutions are the wars of the movement, the campaigns of the party.

The nation is as much a stranger to armed government as it is to armed revolution; but if it is the case that a revolutionary party is more immediately worried than the nation by the governing party, it will also be the case that one day the nation worried in its turn will complain about the government, and that it will be in that precise moment that it will win the moral support of the people, that the revolutionary party will wage battle.

From there, this kind of public recognition leads to bloody rabble-rousing, which under the pompous title of revolutions, hides the impertinence of a few valets rushing to become masters.

When the people have understood the position that has been reserved for them in these Saturnalias they pay for, when they have realized the ignoble and stupid role that they have been made to play, they will know that armed revolution is a heresy from the point of view of principles; they will know that violence is antipodal to right; and once resolved on the morality and the inclinations of the violent parties, whether those of government or revolutionary, there will be a revolution among them brought about by the single force of right: the force of inertia, the denial of assistance. In the denial of assistance will be the repeal of the laws on legal assassination and the proclamation of equity.

This supreme act of national sovereignty I see happen here, not as a calculated result, but as an expression of the law of necessity, as an inevitable product of an administrative avidity, of the extinction of credit and the gloomy arrival of destitution. This revolution, which will be French and not solely Parisian, will tear France from Paris to lead it back to a municipality; then, and only then, will the national sovereignty become fact, since it will be founded on the sovereignty of the commune.

To these words of sovereignty of the commune, all the great minds, who have dragged patriotism to the bar of vocabulary to make the Republic a question of words, exclaim in admiration the name three times holy of unity.

Unity! The time is ripe speak about it. In the midst of the divisions tearing the country apart, I ask what has been made of national unity by the lame paraders who speak in its name!

Unity! I know of only one way to destroy it; that is to want to constitute it by force. If someone had the power to act on the planets, and if, under the pretext of constituting the unity of the solar system, he tried to make them adhere by force to the center, he would destroy the equilibrium and reestablish chaos.

There is someone here who supports unity more than anyone else; that someone is the French people; and if France does not understand that she must promptly leave the stomach of the administration, or else be dissolved there, that will not be my fault, nor the fault of the coarse peritoneum which elaborate the digestion.

XXIII

Let us say, moreover, that the result of an armed revolution, supposing that the revolution is generously interpreted by a kindhearted man, all-powerful over opinion, honest, disinterested and democratic like Washington, the result of an armed revolution, I have said, can turn to the profit of public law.

The tyrants overturned, before others come to take their place, there always appears, on top of the ruins of the tyranny, a man greater than the others, a man whom everyone sees, whom everyone hears, and he is the master of the debris; it is up to him to scatter it or reconstruct it.

If Monsieur de Lamartine had had the genius of action, as he had genius of matters of intelligence, 24 February would have been the date of the French Republic, instead of being nothing but invective.

France, on that day, had expected everything from that man, to whom national sympathies had spontaneously handed over the puissant steering of the destiny of the people.

He only had to say to us in the harmonious rhythm of his beautiful language: “The government of the king is abolished: France is no longer at the Hôtel de Ville!â€

“Your masters have gone and they will not be replaced!â€

“Their law was in force; it is in force no longer. It will not return!â€

“You are returned to yourselves; the foreigner will learn from me that you are free.â€

“Keep a watch over yourselves; I’ll keep a watch on the borders!â€

Certainly, after declarations so substantial, our representatives, whoever they had been, would not have lost sight of the fact that they had to define national law, and not the frenzied law of governments.

Perhaps Monsieur de Lamartine would have perished, a victim of ambitious men left without prey. The despair of the apprentice tyrants might perhaps have been unleashed on him; but his death, like that of all great citizens, would have been fecund! And since, as he said, ideas vegetate in human blood, his would have remained at the beginning of the free era, as an eternal protestation against the tyranny of the delivered.

Unfortunately, instead of scattering the elements of despotism, he set about collecting them together again in order to reassemble them; today the building is complete except for the keystone. It is not he that lives in it, but it is inhabited; not too much worse, perhaps, but not much better either.

Ah, well! the time has come to leave words and come to action!

The time has come to know what democracy wants to say!

The time has arrived for all Frenchmen, in whose arteries still beats a little Gallic blood, who, from Diocletian to Charlemagne, protested against the tyranny of the empire, to assume their position as free citizens, and to call to account the cowardice and the inability of the men of the people, the Republican individualities, for our collapsed credit, for our vanished capital, for our paralyzed industries, for our lay-offs, for our extinguished trade, for our products without market; for our France, finally, so unproductive, so alienated, so venal, so prostituted, so debased, so inhospitable, so foreign to ourselves, so polluted by the tax authorities, and so close to contempt for its children, that they will soon not have enough love in their hearts to set their courage against attempts by their ravishers!

The time has come, for we are facing a decisive spectacle: on one side there is the government which defies the nation;

On the other side, there is the nation which defies the government.

Well, it must be, by complete necessity, that either the government devours the country or that the country absorbs the government.

END

[Translation by Collective Reason (Robert Tucker, Jesse Cohn, and Shawn P. Wilbur.) Robert did most of the hard work, and I'm responsible for the final choices.]

Read the whole thing at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth.

posted 10:41 pm at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth | no comments

Now available thanks to Shawn P. Wilbur at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth:

[Part 1] - [Part 2]

XIII

But there are people who remain far from accepting this reasoning. The theoreticians, our masters, find idea preferable to fact. And this doctrine that they maintain provides them with a dividend which strongly encourages them to continue maintaining it.

In their view, provided that tax payments continue and provided that the rain respects the words Republic and Liberty on the front of public buildings, we are republicans and free.

These people are very powerful!

As powerful as that well-advised character of Arab proverbs who, without touching in any way the contents of a vase, believed that in changing the label, he changed the liqueur.

As powerful as those burlesque geniuses in the farces at the fair, who believe their clothes safe from catching alight because they have on their chest boards carrying assurances against fire.

These people, I repeat, are extraordinarily powerful!

Listening attentively to the intricacies of their arguments, we hear much spoken—and loudly—of the sovereignty of the people. Do you believe it has ever been permitted to insult the sovereign? You reply: No? Ah, well! That is because you were told that the people are sovereign and that you do not have the right to insult the people? I would like better, for my part, to deny the sovereignty of the people and believe in the sovereignty of the government that I am required to respect.

I say that I would rather believe in the sovereignty of government; I am forced to believe in it, everyone is forced to believe in it like me; I do not exist, no one exists for himself; our existence is not at all our own. We do not live civilly, commercially, industrially, religiously, or intellectually except for the government.

Can we travel without a safe-conduct pass signed by it? Can we buy a property or make a transaction without it intervening? Can we profess a religion which it has not validated? Can we teach ourselves other than in the schools and with the books approved by its university? Can we publish anything other than what it permits us to publish? And to push these considerations of this regulating tyranny to the extremes of triviality: can we smoke a cigar which it has not itself sold to us? Are we lawyers, medics, teachers, merchants, artists, agents, town criers, without it giving us a license? No! We do not exist, I say to you, we are inert objects, parts belonging to a conscious and complicated machine whose crank handle is in Paris!

Well, I say that this is an irregular situation, a situation as embarrassing for the government as it is fatal for the nation.

I can understand that it was possible to for Richelieu to govern like this; the France of past centuries was completely and voluntarily under the crown of the king. But woe to those who do not take note of the difference in the times! Today, every citizen feels and deliberates for himself, and control of official acts is everywhere!

XIV

There are, however, in the healthy part of the nation, in the core of good public sense, people who fear to look clearly at the situation; people who cannot resolve themselves to understand that in desperately bleeding themselves to maintain five hundred thousand employees and as many soldiers, they hold back a million men from production and create, to the benefit of I do not know which Minotaur, an official parasitism whose formidable manner dries up in the heart of the country the confidence and credit that is just that source on which this same parasitism comes meanwhile to quench itself.

They perpetuate the crisis and they perpetuate it because they are afraid!

They are afraid of the socialists, and they fear for their property; they are afraid for their religion, they are afraid for their family!

They are afraid of socialists? ... Of which socialists are they afraid?

There are the socialists of Fourier.

There are the socialists of Pierre Leroux.

There are the socialists of Proudhon.

There are the socialists of Considerant.

There are the socialists of Louis Blanc.

There are the socialists of Cabet.

There are, in fact, socialists that I know, and then those that I do not know and that I shall never know, because socialism fragments, subdivides, diversifies itself and separates into factions like everything that is not defined. Well, socialism is not defined.

Socialism is, in short, a very obscure philosophical system, highly complicated, extraordinarily confusing, that erudite men are obliged to study in minute detail to arrive most often at not understanding anything at all.

Socialism, according to what it is possible to grasp from all its proposals, wants to make of society a huge hive into each pigeon-hole of which will be placed a citizen, who will be enjoined to remain silent and wait patiently, while alms are made of his own money. The major dispensers of these alms, supreme tax-collectors of universal revenues, will create a general staff, reasonably well endowed, which on getting up in the morning deigns to satisfy the public appetite; and which, if it sleeps in longer than usual, will leave thirty-six million men without food.

Socialism is an attempt at geometric equilibrium whose demonstration—based on a principle of immobility—does not know to have for its foundation human societies essentially active and progressive. Socialism is an abstract speculation, just as the current administration is an abstract speculation; the people who do not understand the latter do not understand the former either. Well, the people never freely adopt what they do not at all understand.

Socialism, in short, wants to carry on the affairs of the people, and for that it has come too late, or I am much mistaken.

But the socialists are philosophers who have the same right to teach their doctrines as their adversaries have to teach theirs. Just as the people have the right to judge the latter, they have the right to appraise the former.

No one can put himself in the place of the people to pronounce condemnation or recognition of the excellence of a doctrine; since in that diversity of tastes and inclinations that mottle society, there is no doctrine that is bad for all, nor is there one that is good for all.

Tolerance, in theological order, has not resolved the problem of civil concord; the problem rests also on tolerance in social and political order.

State religions have caused, during the centuries, discords and massacres which we now find pitiable.

State doctrines have at the current time caused so much blood to flow that our children gather together to erect a monument to our shame.

We have eliminated state religions; why do we wait to crush state doctrines?

If we do not see any problem with those who wish to have churches, temples or synagogues constructed, at their expense, on land that belongs to them as their own; I do not at all see any problem with those who wish to construct convents, phalansteries or palaces, at their expense, on land that belongs to them as their own.

And if it is simple enough to let the Catholics, the protestants and the Jews have the right to maintain, at their respective expense, in the churches, the temples and the synagogues, the priests, ministers and rabbis; it is just as simple for the monks, socialists and men of court to have the right to maintain, at their expense, in the convents, in the phalansteries, in the palaces, the superiors, the patriarchs and the princes.

All these things fall within the accommodation of the taste, of the faith, of the conscience of each one of us, and it is perhaps possible that one can be a monk, a socialist, a man of court and an excellent citizen at the same time, since the religions, which must remain outside the laws of the State, do not dispense at all with obedience to the laws of the State.

But what includes at least as much buffoonery as strangeness is the determination made by a myriad of systems to attempt political campaigns, and their respective pretensions to make the whole country contribute to the costs of their establishment and the inauguration of their authority in the name of the public and the nation!

We only need to provide a circus acrobat with five hundred thousand bayonets for the act to become a social doctrine and for the wishes and caprices of Pulcinella to be made into the laws of State. We are, certainly, very near to arriving there, and it surprises me that we are not there already.

But I have digressed enough on that subject. Let us return.

XV

They have fear for their property, fear for their religion, fear for their family?

The ultimate sectarians of intolerance, those that babble among us in that language—still unintelligible, alas!—of the tyrants of humanity, repeat without ceasing their disheveled sentences on the subject of religion, of property, of family.

These ridiculous defenders of God and of society lack the intelligence to understand that the ability to save that which they ascribe to necessarily implies the ability to lose it; they do not perceive, as seriously as they take their puerile Quixotism, that the guard they mount at the temple door and at home puts, in their eyes, God and society at their discretion. It just does not enter the heads of these great children, that while saying to God and to society “we have saved you from destruction,†it is as if they were saying “it has depended on us that you continue to exist; you owe us your life.â€

Do you see an articulated apparatus of organic life, claiming a right to the initiative on the existence of God and society?

Do you see here the moral and material universe under the dependence of a degenerate quadrumane which could be finished off with just a fillip or a catarrh?

Shame and pity!

Enough of this wretched and discordant bragging!

Enough of this grandeur founded on the abasement of the public!

Enough of this audacity built on fear!

Religion, property, and the family have survived Geneva rationalism, the philosophy of Voltaire, forfeiture agreements, and the dissolution of social ties from antiquity; religion, property, and the family are, in fact, unassailable by individuals. To defend them is to exploit them! To protect them is to plunder them!

How well the intriguers of every hue—those who believe themselves powerful enough to threaten these institutions as much as those who claim the ability to defend them, all those, in a word, who, living by intimidation and terrorism, have an interest in perpetuating universal panic—how well do all these know that religion, property, and the family have never had a more efficacious protector than time; there has, consequently, never been a possibility of their being attacked other than by time.

Time, without anyone taking any notice, without anyone formulating a complaint, time modifies them all: religion, property, and the family. The current state of the Church with its degenerate discipline and its neutrality in secular politics would make the audacious Hildebrand die of a fit of rage.

The current state of property, with its breaking up into an infinite number of pieces and the melancholic handing over of the chateaus, would bring despair to the great tenants of the last century.

The current state of the family, with the incessant displacement of individuals, the submission to the domestic yoke, the separation resulting from cosmopolitanism, would profoundly wound the patriarchal traditions of our ancestors.

The goings-on of future generations, if we were to see them, would shock our prejudices, our customs, our way of life.

Thus, everything changes without destroying itself, and the human spirit only accepts that for which it is prepared. Every day, it opens itself to new interests, to which it can accommodate itself without shock. After a period of time, the coming together of interests gives rise to a new institution, which, having arrived en bloc beforehand, would have surprised and injured everyone, but having arrived in a providential way has not hurt anyone and has satisfied all.

Let us speak and have no fear.

Fear is nothing but the condemnation of oneself, and once one is condemned there is no shortage of executioners.

XVI

The hypothesis of spoliation has been put forward.

No one can believe in the corruptibility of the majorities, without denying at the same time human reason and the principle of its demonstration. If the majorities are incorruptible, they are equitable, since the basic law of equity is respect for acquired right.

Acquired right has been respected even among people where the means of acquisition have been denied to the majority. How can this right be violated among us, where the acquisition, as much as it is still impeded, can nonetheless be considered public.

Let one not speak to me of brigandage, when it is substantiated that it is only carried out by minorities and that its exercise requires its organization.

Let one not speak to me of brigandage, when in the place of a plan by some unacceptable organization one brings me some shouts in the street or some argument at a club.

The people are not responsible for the exceptional insanity of a few spirits. The mad are the lost children of humanity.

Brigandage is not organizable. I am wrong, one can organize it, and here is how: put in each commune an authority more jealous of individual law than public law; establish in each arrondissement, in each department hateful magistrates, intolerant and fanatical; put at the top of this hierarchy a supreme head, blinded by the pride of domination and nourished by impious dogmas; give to this man four or five thousand armed men for support, and spoliation as a rallying call and the violation of acquired rights is consummated. But one says to me that this picture is of nothing but administrative organization, founded on the constitution. I avow it, and what follows from it that a malefactor who does not embrace the administration of the State would be nothing to fear. But this also amounts to saying that this administration squashes us in some way, that we are at the complete mercy of anyone bold enough that chance can allow to happen.

Give the people spoliation as a rallying call and this rallying call will encase itself in the probity of numbers.

How this rallying call goes out from the administration, the systematic webs of which embrace all individuals and all the territory, and the supreme thought propagates like electricity to be lost in blood!

Such is the only possible organization of brigandage, and such is, finally, a usage perhaps applied by the government of representative monarchies.

Those that own, do they fear that they might be individually plundered by those who do not? I sympathize with them while being able to condemn them, because by that they tell me themselves what they would be disposed to do if they had nothing.

And, yet, they err; they are more honest people than they think. They reason from the point of view of the needs that their fortune has given them. I understand that if they were suddenly deprived of the satisfaction of these needs, which have become for them, in some way, natural, they would have to suffer, and that it is under this impression that they argue. But there is one thing that they forget, that is, that if they had never had their fortune, they would not have had their needs either.

Is it not, moreover the case, by virtue of the same principle, that he who would come to dispossess me today, could himself be dispossessed tomorrow? And if things go on like that with each dispossessing the other, what is going to become of production?

Can such an absurd state of things perhaps be understood by sensible people, where the day after a revolution where everything is at the discretion of the masses, and where perversity, in the state of emergency, finds itself drowned in public probity?

If the majority, who do not own anything, had an instinct for plunder, it would have been a long time since the minority who owned anything had anything left.

If there are criminals in our communities, let us count them; it is an easy job; and if we find a few or if we do not find any, we are not going to believe that we exercise here the monopoly of equity: people are the same everywhere.

If the domineering and insolent rage of a few men tear to shreds popular magnanimity and bring into disrepute human character, it follows that the dogma of improbity is the rationale of tyrannies, and the security of tyrants is based on the hatred and mistrust of citizens among themselves.

As for me, separated from the parties to remain human, I defend humanity with esprit de corps.

XVII

But here is what I hear said:

If socialism comes into power, it would be able to compel its recognition. That objection, I expect.

It is quite true that as philosophers, as apostles of a doctrine, as teachers, the socialists have are not at all frightening. All of their opinions might therefore be expressed without danger, seeing that these opinions do not at all aspire to government.

Well, so! Do we think that good public sense would make justice of the absurd, and we fear being governed by the absurd? Do we feel thus that one could govern us contrary to good sense? Do we feel thus that one could violate, surprise our religion as soon as one comes to govern us? But, that admitted, we are incessantly in danger of being handed over! What I say is that, being in danger, we have already been handed over; because, in matters of public security, probabilities are certainties.

At the moment when we recognize that one could do violence to us one does violence to us; it is an inevitable law, inescapable and inherent in all states of dependence.

It is therefore not the socialists that it is necessary to fear, that it is necessary to exorcise; it is necessary to fear, it is necessary to exorcise the institution of government, by virtue of the fact that it can strike us. This institution alone is bad, is dangerous, and whoever is put at the head of this institution will immediately be as dangerous as the socialists; first, because he can become the institution, and second, because he can be surprised and conquered by the socialists, and, finally, because his system can be as bad as, or worse than, theirs.

As long as there is no untrammeled freedom of opinion in France, in order for a doctrine to emerge, it will be forced to attempt the overthrow of the government, for its sole means of action will be to become official State doctrine, to govern; and as long as an official State doctrine governs, it will necessarily consider other doctrines as dangerous rivals and proscribe them.

Thus it is that we continue to see these vicious struggles to which society lends its children and its money, these battles of scheming and ambition that I would call ridiculous if they weren’t so atrocious, and of which the outcome—those outcast today to be lauded tomorrow—makes criminality or heroism a mere question of the date.

XVIII

It is therefore shown that socialism is no more to be feared in itself than any other philosophical doctrine. It is established that it can become dangerous only in the condition of governing. That comes down to saying that nothing is dangerous which does not govern; from this it follows that whoever governs is already or can become dangerous—and the strict consequence is still that the nation can have no other public enemy than the government.

That having been said, it is beyond doubt that the only important thing in modern times, as well as the only one against which our representatives have not prepared themselves, consists in simplifying the administrative organism to the degree demanded by individual liberty, which has been without guarantee until this day, and by the reduction of taxation, which will be impossible to do as long as we persist on the path already beaten by the governments with its fat budgets.

The present governmental institution is the same as that of last year, and that of last year resumes all the powers of Louis XIV, with the sole exception that the unity of action of the royal trust finds itself re-divided among six or seven ministerial departments set up by a parliamentary majority. Can we be a free people, as long as our entire existence, from the civil order to the hygienic order, will be so regulated?

If we posit the guarantee of our individual liberty, if we resolve to move ourselves by our own movement, the nation will acquire again that power of which it was relieved or that has been usurped from it; that necessary power, indispensable to the balance of popular prerogatives with governmental initiative.

If the nation recovered its strength, the assembly, which comes from its own ranks, would not soon forget its real master, where true sovereignty lies, and in the contract that would be set forth between France and its stewards, there would remain no means for the latter to make themselves masters of the former.

[to be concluded...]

[Translation by Collective Reason (Robert Tucker, Jesse Cohn, and Shawn P. Wilbur.) Robert did most of the hard work, and I'm responsible for the final choices.]

Read the whole thing at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth.

posted 8:51 pm at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth | no comments

Now available thanks to Shawn P. Wilbur at Out of the Libertarian Labyrinth:

[Part 1] - [Part 2]

XIII

But there are people who remain far from accepting this reasoning. The theoreticians, our masters, find idea preferable to fact. And this doctrine that they maintain provides them with a dividend which strongly encourages them to continue maintaining it.

In their view, provided that tax payments continue and provided that the rain respects the words Republic and Liberty on the front of public buildings, we are republicans and free.

These people are very powerful!

As powerful as that well-advised character of Arab proverbs who, without touching in any way the contents of a vase, believed that in changing the label, he changed the liqueur.

As powerful as those burlesque geniuses in the farces at the fair, who believe their clothes safe from catching alight because they have on their chest boards carrying assurances against fire.

These people, I repeat, are extraordinarily powerful!

Listening attentively to the intricacies of their arguments, we hear much spoken—and loudly—of the sovereignty of the people. Do you believe it has ever been permitted to insult the sovereign? You reply: No? Ah, well! That is because you were told that the people are sovereign and that you do not have the right to insult the people? I would like better, for my part, to deny the sovereignty of the people and believe in the sovereignty of the government that I am required to respect.

I say that I would rather believe in the sovereignty of government; I am forced to believe in it, everyone is forced to believe in it like me; I do not exist, no one exists for himself; our existence is not at all our own. We do not live civilly, commercially, industrially, religiously, or intellectually except for the government.

Can we travel without a safe-conduct pass signed by it? Can we buy a property or make a transaction without it intervening? Can we profess a religion which it has not validated? Can we teach ourselves other than in the schools and with the books approved by its university? Can we publish anything other than what it permits us to publish? And to push these considerations of this regulating tyranny to the extremes of triviality: can we smoke a cigar which it has not itself sold to us? Are we lawyers, medics, teachers, merchants, artists, agents, town criers, without it giving us a license? No! We do not exist, I say to you, we are inert objects, parts belonging to a conscious and complicated machine whose crank handle is in Paris!

Well, I say that this is an irregular situation, a situation as embarrassing for the government as it is fatal for the nation.

I can understand that it was possible to for Richelieu to govern like this; the France of past centuries was completely and voluntarily under the crown of the king. But woe to those who do not take note of the difference in the times! Today, every citizen feels and deliberates for himself, and control of official acts is everywhere!

XIV

There are, however, in the healthy part of the nation, in the core of good public sense, people who fear to look clearly at the situation; people who cannot resolve themselves to understand that in desperately bleeding themselves to maintain five hundred thousand employees and as many soldiers, they hold back a million men from production and create, to the benefit of I do not know which Minotaur, an official parasitism whose formidable manner dries up in the heart of the country the confidence and credit that is just that source on which this same parasitism comes meanwhile to quench itself.

They perpetuate the crisis and they perpetuate it because they are afraid!

They are afraid of the socialists, and they fear for their property; they are afraid for their religion, they are afraid for their family!

They are afraid of socialists? ... Of which socialists are they afraid?

There are the socialists of Fourier.

There are the socialists of Pierre Leroux.

There are the socialists of Proudhon.

There are the socialists of Considerant.

There are the socialists of Louis Blanc.

There are the socialists of Cabet.

There are, in fact, socialists that I know, and then those that I do not know and that I shall never know, because socialism fragments, subdivides, diversifies itself and separates into factions like everything that is not defined. Well, socialism is not defined.

Socialism is, in short, a very obscure philosophical system, highly complicated, extraordinarily confusing, that erudite men are obliged to study in minute detail to arrive most often at not understanding anything at all.

Socialism, according to what it is possible to grasp from all its proposals, wants to make of society a huge hive into each pigeon-hole of which will be placed a citizen, who will be enjoined to remain silent and wait patiently, while alms are made of his own money. The major dispensers of these alms, supreme tax-collectors of universal revenues, will create a general staff, reasonably well endowed, which on getting up in the morning deigns to satisfy the public appetite; and which, if it sleeps in longer than usual, will leave thirty-six million men without food.

Socialism is an attempt at geometric equilibrium whose demonstration—based on a principle of immobility—does not know to have for its foundation human societies essentially active and progressive. Socialism is an abstract speculation, just as the current administration is an abstract speculation; the people who do not understand the latter do not understand the former either. Well, the people never freely adopt what they do not at all understand.

Socialism, in short, wants to carry on the affairs of the people, and for that it has come too late, or I am much mistaken.

But the socialists are philosophers who have the same right to teach their doctrines as their adversaries have to teach theirs. Just as the people have the right to judge the latter, they have the right to appraise the former.

No one can put himself in the place of the people to pronounce condemnation or recognition of the excellence of a doctrine; since in that diversity of tastes and inclinations that mottle society, there is no doctrine that is bad for all, nor is there one that is good for all.

Tolerance, in theological order, has not resolved the problem of civil concord; the problem rests also on tolerance in social and political order.

State religions have caused, during the centuries, discords and massacres which we now find pitiable.

State doctrines have at the current time caused so much blood to flow that our children gather together to erect a monument to our shame.

We have eliminated state religions; why do we wait to crush state doctrines?

If we do not see any problem with those who wish to have churches, temples or synagogues constructed, at their expense, on land that belongs to them as their own; I do not at all see any problem with those who wish to construct convents, phalansteries or palaces, at their expense, on land that belongs to them as their own.

And if it is simple enough to let the Catholics, the protestants and the Jews have the right to maintain, at their respective expense, in the churches, the temples and the synagogues, the priests, ministers and rabbis; it is just as simple for the monks, socialists and men of court to have the right to maintain, at their expense, in the convents, in the phalansteries, in the palaces, the superiors, the patriarchs and the princes.

All these things fall within the accommodation of the taste, of the faith, of the conscience of each one of us, and it is perhaps possible that one can be a monk, a socialist, a man of court and an excellent citizen at the same time, since the religions, which must remain outside the laws of the State, do not dispense at all with obedience to the laws of the State.

But what includes at least as much buffoonery as strangeness is the determination made by a myriad of systems to attempt political campaigns, and their respective pretensions to make the whole country contribute to the costs of their establishment and the inauguration of their authority in the name of the public and the nation!

We only need to provide a circus acrobat with five hundred thousand bayonets for the act to become a social doctrine and for the wishes and caprices of Pulcinella to be made into the laws of State. We are, certainly, very near to arriving there, and it surprises me that we are not there already.

But I have digressed enough on that subject. Let us return.

XV

They have fear for their property, fear for their religion, fear for their family?

The ultimate sectarians of intolerance, those that babble among us in that language—still unintelligible, alas!—of the tyrants of humanity, repeat without ceasing their disheveled sentences on the subject of religion, of property, of family.

These ridiculous defenders of God and of society lack the intelligence to understand that the ability to save that which they ascribe to necessarily implies the ability to lose it; they do not perceive, as seriously as they take their puerile Quixotism, that the guard they mount at the temple door and at home puts, in their eyes, God and society at their discretion. It just does not enter the heads of these great children, that while saying to God and to society “we have saved you from destruction,†it is as if they were saying “it has depended on us that you continue to exist; you owe us your life.â€

Do you see an articulated apparatus of organic life, claiming a right to the initiative on the existence of God and society?

Do you see here the moral and material universe under the dependence of a degenerate quadrumane which could be finished off with just a fillip or a catarrh?

Shame and pity!

Enough of this wretched and discordant bragging!

Enough of this grandeur founded on the abasement of the public!

Enough of this audacity built on fear!

Religion, property, and the family have survived Geneva rationalism, the philosophy of Voltaire, forfeiture agreements, and the dissolution of social ties from antiquity; religion, property, and the family are, in fact, unassailable by individuals. To defend them is to exploit them! To protect them is to plunder them!

How well the intriguers of every hue—those who believe themselves powerful enough to threaten these institutions as much as those who claim the ability to defend them, all those, in a word, who, living by intimidation and terrorism, have an interest in perpetuating universal panic—how well do all these know that religion, property, and the family have never had a more efficacious protector than time; there has, consequently, never been a possibility of their being attacked other than by time.

Time, without anyone taking any notice, without anyone formulating a complaint, time modifies them all: religion, property, and the family. The current state of the Church with its degenerate discipline and its neutrality in secular politics would make the audacious Hildebrand die of a fit of rage.

The current state of property, with its breaking up into an infinite number of pieces and the melancholic handing over of the chateaus, would bring despair to the great tenants of the last century.

The current state of the family, with the incessant displacement of individuals, the submission to the domestic yoke, the separation resulting from cosmopolitanism, would profoundly wound the patriarchal traditions of our ancestors.

The goings-on of future generations, if we were to see them, would shock our prejudices, our customs, our way of life.

Thus, everything changes without destroying itself, and the human spirit only accepts that for which it is prepared. Every day, it opens itself to new interests, to which it can accommodate itself without shock. After a period of time, the coming together of interests gives rise to a new institution, which, having arrived en bloc beforehand, would have surprised and injured everyone, but having arrived in a providential way has not hurt anyone and has satisfied all.

Let us speak and have no fear.

Fear is nothing but the condemnation of oneself, and once one is condemned there is no shortage of executioners.

XVI

The hypothesis of spoliation has been put forward.

No one can believe in the corruptibility of the majorities, without denying at the same time human reason and the principle of its demonstration. If the majorities are incorruptible, they are equitable, since the basic law of equity is respect for acquired right.

Acquired right has been respected even among people where the means of acquisition have been denied to the majority. How can this right be violated among us, where the acquisition, as much as it is still impeded, can nonetheless be considered public.

Let one not speak to me of brigandage, when it is substantiated that it is only carried out by minorities and that its exercise requires its organization.

Let one not speak to me of brigandage, when in the place of a plan by some unacceptable organization one brings me some shouts in the street or some argument at a club.

The people are not responsible for the exceptional insanity of a few spirits. The mad are the lost children of humanity.

Brigandage is not organizable. I am wrong, one can organize it, and here is how: put in each commune an authority more jealous of individual law than public law; establish in each arrondissement, in each department hateful magistrates, intolerant and fanatical; put at the top of this hierarchy a supreme head, blinded by the pride of domination and nourished by impious dogmas; give to this man four or five thousand armed men for support, and spoliation as a rallying call and the violation of acquired rights is consummated. But one says to me that this picture is of nothing but administrative organization, founded on the constitution. I avow it, and what follows from it that a malefactor who does not embrace the administration of the State would be nothing to fear. But this also amounts to saying that this administration squashes us in some way, that we are at the complete mercy of anyone bold enough that chance can allow to happen.

Give the people spoliation as a rallying call and this rallying call will encase itself in the probity of numbers.

How this rallying call goes out from the administration, the systematic webs of which embrace all individuals and all the territory, and the supreme thought propagates like electricity to be lost in blood!

Such is the only possible organization of brigandage, and such is, finally, a usage perhaps applied by the government of representative monarchies.

Those that own, do they fear that they might be individually plundered by those who do not? I sympathize with them while being able to condemn them, because by that they tell me themselves what they would be disposed to do if they had nothing.

And, yet, they err; they are more honest people than they think. They reason from the point of view of the needs that their fortune has given them. I understand that if they were suddenly deprived of the satisfaction of these needs, which have become for them, in some way, natural, they would have to suffer, and that it is under this impression that they argue. But there is one thing that they forget, that is, that if they had never had their fortune, they would not have had their needs either.

Is it not, moreover the case, by virtue of the same principle, that he who would come to dispossess me today, could himself be dispossessed tomorrow? And if things go on like that with each dispossessing the other, what is going to become of production?

Can such an absurd state of things perhaps be understood by sensible people, where the day after a revolution where everything is at the discretion of the masses, and where perversity, in the state of emergency, finds itself drowned in public probity?

If the majority, who do not own anything, had an instinct for plunder, it would have been a long time since the minority who owned anything had anything left.

If there are criminals in our communities, let us count them; it is an easy job; and if we find a few or if we do not find any, we are not going to believe that we exercise here the monopoly of equity: people are the same everywhere.

If the domineering and insolent rage of a few men tear to shreds popular magnanimity and bring into disrepute human character, it follows that the dogma of improbity is the rationale of tyrannies, and the security of tyrants is based on the hatred and mistrust of citizens among themselves.

As for me, separated from the parties to remain human, I defend humanity with esprit de corps.

XVII

But here is what I hear said:

If socialism comes into power, it would be able to compel its recognition. That objection, I expect.

It is quite true that as philosophers, as apostles of a doctrine, as teachers, the socialists have are not at all frightening. All of their opinions might therefore be expressed without danger, seeing that these opinions do not at all aspire to government.

Well, so! Do we think that good public sense would make justice of the absurd, and we fear being governed by the absurd? Do we feel thus that one could govern us contrary to good sense? Do we feel thus that one could violate, surprise our religion as soon as one comes to govern us? But, that admitted, we are incessantly in danger of being handed over! What I say is that, being in danger, we have already been handed over; because, in matters of public security, probabilities are certainties.