Claim Chowder: Ray Kurzweil, “2009,” in The Age of Spiritual Machines posted by Rad Geek at Rad Geek People's Daily » Over My Shoulder 31 Dec 2009 3:00 pm

Welcome to The World of Tomorrow, everyone. This is from Chapter 9 of Ray Kurzweil’s 1999 exercise in Singularity futurism, The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence. The chapter is entitled 2009,

and it’s supposed to tell us what the world would be like by, well, now. It’s long, so I’ll let you know now that I have some commentary below.

(Oh, and in case you’re curious, the weird exchange at the end is this goofy technique that Kurzweil uses at the end of each chapter in the book. It’s supposed to be a dialogue with his imagined reader. So, yeah.)

2009

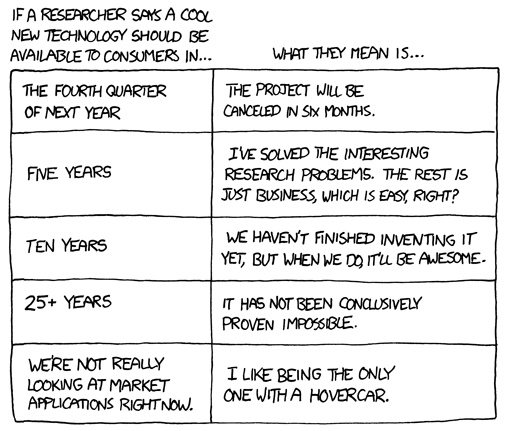

It is said that people overestimate what can be accomplished in the short term, and underestimate the changes that will occur in the long term. With the pace of change continuing to accelerate, we can consider even the first decade in the twenty-first century to constitute a long-term view. With that in mind, let us consider the beginning of the next century.

The Computer Itself

It is now 2009. Individuals primarily use portable computers, which have become dramatically lighter and thinner than the notebook computers of ten years earlier. Personal computers are available in a wide range of sizes and shapes, and are commonly embedded in clothing and jewelry such as wristwatches, rings, earrings, and other body ornaments. Computers with a high-resolution visual interface range from rings and pins and credit cards up to the size of a thin book.

People typically have at least a dozen computers on and around their bodies, which are networked using

body LANs(local area networks).[1] These computers provide communication facilities similar to cellular phones, pagers, and web surfers, monitor body functions, provide directions for navigation, and a variety of other services.For the most part, these truly personal computers have no moving parts. Memory is completely electronic, and most portable computers do not have keyboards.

Rotating memories (that is, computer memories that use a rotating platen, such as hard drives, CD-ROMs, and DVDs) are on their way out, although rotating magnetic memories are still used in

servercomputers where large amounts of information are stored. Most users have servers in their homes and offices where they keep large stores of digitalobjects,including their software, databases, documents, music, movies, and virtual-reality environments (although these are still at an early stage). There are services to keep one’s digital objects in central repositories, but most people prefer to keep their private information under their own physical control.Cables are disappearing.[2] Communication between components, such as pointing devices, microphones, displays, printers, and the occasional keyboard, uses short-distance wireless technology.

Computers routinely include wireless technology to plug into the ever-present worldwide network, providing reliable, instantly available, very-high-bandwidth communication. Digital objects such as books, music albums, movies, and software are rapidly distributed as data files through the wireless network, and typically do not have a physical object associated with them.

The majority of text is created using continuous speech recognition (CSR) dictation software, but keyboards are still used. CSR is very accurate, far more so than the human transcriptionists who were used up until a few years ago.

Also ubiquitous are language user interfaces (LUIs), which combine CSR and natural language understanding. For routine matters, such as simple business transactions and information inquiries, LUIs are quite responsive and precise. They tend to be narrowly focused, however, on specific types of tasks. LUIs are frequently combined with animated personalities. Interacting with an animated personality to conduct a purchase or make a reservation is like talking to a person using videoconferencing, except that the person is simulated.

Computer displays have all the display qualities of paper—high resolution, high contrast, large viewing angle, and no flicker. Books, magazines, and newspapers are now routinely read on displays that are the size of, well, small books.

Computer displays built into eyeglasses are also used. These specialized glasses allow users to see the normal visual environment, while creating a virtual image that appears to hover in front of the viewer. The virtual images are created by a tiny laser built into the glasses that projects the images directly onto the user’s retinas.[3]

Computers routinely include moving picture image cameras and are able to reliably identify their owners from their faces.

In terms of circuitry, three-dimensional chips are commonly used, and there is a transition taking place from the older, single-layer chips.

Sound producing speakers are being replaced with very small chip-based devices that can place high resolution sound anywhere in three-dimensional space. This technology is based on creating audible frequency sounds from the spectrum created by the interaction of very high frequency tones. As a result, very small speakers an createvery robust three-dimensional sound.

A $1,000 personal computer (in 1999 dollars) can perform about a trillion calculations per second.[4] Supercomputers match at least the hardware capacity of the human brain—20 million billion calculations per second.[5] Unused computers on the Internet are being harvested, creating virtual parallel supercomputers with human brain hardware capacity.

There is increasing interest in massively parallel neural nets, genetic algorithms, and other forms of

chaoticor complexity theory computing, although most computer computations are still done using conventional sequential processing, albeit with some limited parallel processing.Research has been initiated on reverse engineering the human brain through both destructive scans of the brains of recently deceased persons as well as non-invasive scans using high resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of living persons.

Autonomous nanoengineered machines (that is, machines constructed atom by atom and molecule by molecule) have been demonstrated and include their own computational controls. However, nanoengineering is not yet considered a practical technology.

Education

In the twentieth century, computers in schools were mostly on the trailing edge, with most effective learning from computers taking place in the home. Now in 2009, while schools are still not on the cutting edge, the profound importance of the computer as a knowledge tool is widely recognized. Computers play a central role in all facets of education, as they do in other spheres of life.

The maority of reading is done on displays, although the

installed baseof paper documents is still formidable. The generation of paper documents is dwindling, however, as books and other papers of largely twentieth-century vintage are being rapidly scanned and stored. Documents circa 2009 routinely include embedded moving images and sounds.Students of all ages typically have a computer of their own, which is a thin tabletlike device weighing under a pound with a very high resolution display suitable for reading. Students interact with their computers primarily by voice and by pointing with a device that looks like a pencil. Keyboards still exist, but most textual language is created by speaking. Learning materials are accessed through wireless communication.

Intelligent courseware has emerged as a common means of learning. Recent controversial studies have shown that students can learn basic skills such as reading and math just as readily with interactive learning software as with human teachers, particularly when the ratio of students to human teachers is more than one to one. Although the studies have come under attack, most students and their parents have accepted this notion for years. The traditional mode of a human teacher instructing a group of children is still prevalent, but schools are increasingly relying on software approaches, leaving human teachers to attend primarily to issues of motivation, psychological well-being, and socialization. Many children learn to read on their own using personal computers before entering grade school.

Preschool and elementary school children routinely read at their intellectual level using print-to-speech reading software until their reading skill level catches up. These print-to-speech reading systems display the full image of documents, and can read the print aloud while highlighting what is being read. Synthetic voices sound fully human. Although some educators expressed concern in the early ’00 years that students would rely unduly on reading software, such systems have been readily accepted by children and their parents. Studies have shown that students improve their reading skills by being exposed to synchronized visual and auditory presentations of text.

Learning at a distance (for example, lectures and seminars in which the participants are geographically scattered) is commonplace.

Learning is becoming a significant portion of most jobs. Training and developing new skills is emerging as an ongoing responsibility in most careers, not just an occasional supplement, as the level of skill needed for meaningful employment soars ever higher.

Disabilities

Persons with disabilities are rapidly overcoming their handicaps through the intelligent technology of 2009. Students with reading disabilities routinely ameliorate their disability using print-to-speech reading systems.

Print-to-speech reading machines for the blind are now very small, inexpensive, palm-sized devices that can read books (those that still exist in paper form) and other printed documents, and other real-world text such as signs and displays. These reading systems are equally adept at reading the trillions of electronic documents that are instantly available from the ubiquitous wireless worldwide network.

After decades of ineffective attempts, useful navigation devices have been introduced that can assist blind people in avoiding physical obstacles in their path, and finding their way around, using global positioning system (GPS) technology. A blind person can interact with her personal reading-navigation systems through two-way voice communication, kind of like a Seeing-Eye dog that reads and talks.

Deaf persons—or anyone with a hearing impairment—commonly use portable speech-to-text listening machines, which display a real-time transcription of what people are saying. The deaf user has the choice of either reading the transcribed speech as displayed text, or watching an animated person gesturing in sign language. These have eliminated the primary communication handicap associated with deafness. Listening machines can also translate what is being said into another language in real time, so they are commonly used by hearing people as well.

Computer-controlled orthotic devices have been introduced. These

walking machinesenable paraplegic persons to walk and climb stairs. The prosthetic devices are not yet usable by all paraplegic persons, as many physically disabled persons have dysfunctional joints from years of disuse. However, the advent of orthotic walking systems is providing more motivation to have these joints replaced.There is a growing perception that the primary disabilities of blindness, deafness, and physical impairment do not necessarily impart handicaps. Disabled persons routinely describe their disabilities as mere inconveniences. Intelligent technology has become the great leveler.

Communication

Translating Telephone technology (where you speak in English and your Japanese friend hears you in Japanese, and vice versa) is commonly used for many language pairs. It is a routine capability of an individual’s personal computer, which also serves as her phone.

Telephonecommunication is primarily wireless, and routinely includes high-resolution moving images. Meetings of all kinds and sizes routinely take place among geographically separated participants.There is effective convergence, at least on the hardware and supporting software level, of all media, which exist as digital objects (that is, files) distributed by the ever-present high-bandwidth, wireless information web. Users can instantly download books, magazines, newspapers, television, radio, movies, and other forms of software to their highly portable personal communication devices.

Virtually all communication is digital and encrypted, with public keys available to government authorities. Many individuals and groups, including but not limited to criminal organizations, use an additional layer of virtually unbreakable encryption codes with no third-party keys.

Haptic technologies are emerging that allow people to touch and feel objects and other persons at a distance. These force-feedback devices are widely used in games and in training simulation systems.

Interactive games routinely include all-encompassing visual and auditory environments, but a satisfactory, all-encompassing tactile environment is not yet available. The online chat rooms of the late 1990s have been replaced with virtual environments where you can meet people with full visual realism.

People have sexual experiences at a distance with other persons as well as virtual partners. But the lack of the

surroundtactile environment has thus far kept virtual sex out of the mainstream. Virtual partners are popular as forms of sexual entertainment, but they’re more gamelike than real. And phone sex is a lot more popular now that phones routinely include high-resolution, real-time moving images of the person on the other end.Business and Economics

Despite occasional corrections, the ten years leading up to 2009 have seen continuous economic expansion and prosperity due to the dominance of the knowledge content of products and services. The greatest gains continue to be in the value of the stock market. Price deflation concerned economists in the early ’00 years, but they quickly realized it was a good thing. The high-tech community pointed out that significant deflation had existed in the computer hardware and software industries for many years earlier without detriment.

The United States continues to be the economic leader due to its primacy in popular culture and its entrepreneurial environment. Since information markets are largely world markets, the United States has benefited greatly from its immigrant history. Being comprised of all the world’s peoples—specifically the descendents of people from around the globe who had endured grea risk for a better life—is the ideal heritage for the new knowledge-based economy. China has also emerged as a powerful economic player. Europe is several years ahead of Japan and Korea in adopting the American emphasis on venture capital, employee stock options, and tax policies that encourage entrepreneurship, although these practices have become popular throughout the world.

At least half of all transactions are conducted online. Intelligent assistants which combine continuous speech recognition, natural-language understanding, problem solving, and animated personalities routinely assist with finding information, answering questions, and conducting transactions. Intelligent assistants have become a primary interface for interacting with information-based services, with a wide range of choices available. A recent poll shows that both male and female users prefer female personalities for their computer-based intelligent assistants. The two most popular are Maggie, who claims to be a waitress in a Harvard Square café, and Michelle, a stripper from New Orleans. Personality designers are in demand, and the field constitutes a growth area in software development.

Most purchases of books, musical

albums,videos, games, and other forms of software do not involve any physical object, so new business models for distributing these forms of information have emerged. One shops for these information objects bystrollingthrough virtual malls, sampling and selecting objects of interest, rapidly (and securely) conducting an online transaction, and then quickly downloading the information using high-speed wireless communication. There are many types and gradations of transactions to gain access to thes products. You canbuya book, musical album, video, etcetera, which gives you unlimited personal access. Alternatively, you can rent access to read, view, or listen once, or a few times. Or you can rent access by the minute. Alternatively, access may be limited to a particular computer, or to any computer accessed by a particular person or by a set of persons.There is a strong trend toward the geographic separation of work groups. People are successfully working together despite living and working in different places.

The average household has more than a hundred computers, most of which are embedded in appliances and built-in communications systems. Household robots have emerged, but are not yet fully accepted.

Intelligent roads are in use, primarily for long-distance travel. Once your car’s guidance system locks onto the control sensors on one of these highways, you can sit back and relax. Local roads, though, are still predominantly conventional.

A company west of the Mississippi and north of the Mason-Dixon line has surpassed a trillion dollars in market capitalization.

Politics and Society

Privacy has emerged as a primary political issue. The virtually constant use of electronic communication technologies is leaving a highly detailed trail of every person’s every move. Litigation, of which there has been a great dea, has placed some constraints on the widespread distribution of personal data. Government agencies, however, continue to have the right to gain access to people’s files, which has resulted in the popularity of unbreakable encryption technologies.

There is a growing neo-Luddite movement, as the skill ladder continues to accelerate upward. As with earlier Luddite movements, its influence is limited by the level of prosperity made possible by new technology. The movement does succeed in establishing continuing education as a primary right associated with employment.

There is continuing concern with an underclass that the skill ladder has left fare behind. The size of the underclass appears to be stable, however. Although not politically popular, the underclass is politically neutralized through public assistance and the generally high levels of affluence.

The Arts

The high quality of computer screens, and the facilities of computer-assisted visual rendering software, have made the computer screen a medium of choice for visual art. Most visual art is the result of a collaboration between human artists and their intelligent art software. Virtual paintings—high-resolution wall-hung displays—have become popular. Rather than always displaying the same work of art, as with a conventional painting or poster, these virtual paintings can change the displayed work at the user’s verbal command, or can cycle through collections of art. The displayed artwork can be works by human artists or original art, created in real time by cybernetic art software.

Human musicians routinely jam with cybernetic musicians. The creation of music has become available to persons who are not musicians. Creating music does not necessarily require the fine motor coordination of using traditional controllers. Cybernetic music creation systems allow people who appreciate music but who are not knowledgeable about music theory and practice to create music in collaboration with their automatic composition software. Interactive brain-generated music, which creates a resonance between the user’s brain waves and the music being listened to, is another popular genre.

Musicians commonly use electronic controllers that emulate the playing style of the old acoustic instruments (for example, piano, guitar, violin, drums), but there is a surge of interest in the new

aircontrollers in which you create music by moving your hands, feet, mouth, and other body parts. Other music controllers involve interacting with specially designed devices.Writers use voice-activated word processing; grammar checkers are now actually useful; and distribution of written documents from articles to books typically does not involve paper and ink. Style improvement and automatic editing software is widely used to improve the quality of writing. Language translation software is also widely used to translate written works in a variety of languages. Nevertheless, the core process of creating written language is less affected by intelligent software technologies than the visual and musical arts. However,

cyberneticauthors are emerging.Beyond music recordings, images, and movie videos, the most popular type of digital entertainment object is virtual experience software. These interactive virtual environments allow you to go whitewater rafting on virtual rivers, to hang-glide in a virtual Grand Canyon, or to engage in intimate encounters with your favorite movie star. Users also experience fantasy environments with no counterpart in the physical world. The visual and auditory experience of virtual reality is compelling, but tactile interaction is still limited.

Warfare

The security of computation and communication is the primary focus of the U.S. Department of Defense. There is general recognition that the side that can maintain the integrity of its computational resources will dominate the battlefield.

Humans are generally far removed from the scene of battle. Warfare is dominated by unmanned intelligent airborne devices. Many of these flying weapons are the size of small birds, or smaller.

The United States continues to be the world’s dominant military power, which is largely accepted by the rest of the world, as most countries concentrate on economic competition. Military conflicts between nations are rare, and most conflicts are between nations and smaller bands of terrorists. The greatest threat to national security comes from bioengineered weapons.

Health and Medicine

Bioengineered treatments have reduced the toll from cancer, heart disease, and a variety of other health problems. Significant progress is being made in understanding the information processing basis of disease.

Telemedicine is widely used. Physicians can examine patients using visual, auditory, and haptic examination from a distance. Health clinics with relatively inexpensive equipment and a single technician bring health care to remote areas where doctors had previously been scarce.

Computer-based pattern recognition is routinely used to interpret imaging data and other diagnostic procedures. The use of noninvasive imaging technology has substantially increased. Diagnosis almost always involves collaboration between a human physician and a pattern-recognition-based expert system. Doctors routinely consult knowledge-based systems (generally through two-way voice communication augmented by visual displays), which provide automated guidance, access to the most recent medical research, and practice guidelines.

Lifetime patient records are maintained in computer databases. Privacy concerns about access to these records (as with many other databases of personal information) have emerged as a major issue.

Doctors routinely train in virtual reality environments, which include a haptic interface. These systems simulate the visual, auditory, and tactile experience of medical procedures, including surgery. Simulated patients are available for continuing medical education, for medical students, and for people who just want to play doctor.

Philosophy

There is renewed interest in the Turing Test, first proposed by Alan Turing in 1950 as a means for testing intelligence in a machine. Recall that the Turing Test contemplates a situation in which a human judge interviews the computer and a human

foil,communicating with both over terminal lines. If the human judge is unable to tell which interviewee is human and which is machine, the machine is deemed to possess human-level intelligence. Although computers still fail the test, confidence is increasing that they will be in a position to pass it within another one or two decades.There is serious speculation on the potential sentience (that is, consciousness) of computer-based intelligence. The increasingly apparent intelligence of computers has spurred an interest in philosophy.

… Hey Molly.

Oh, so you’re calling me now.

Well, the chapter was over and I didn’t hear from you.

I’m sorry, I was finishing up a phone call with my fiancé.

Hey, congratulations, that’s great. How long have you known ….

Ben, his name is Ben. We met about ten years ago, just after you finished this book.

I see. So how have I done?

You did manage to sell a few copies.

No, I mean with my predictions.

Not very well. The translating telephones, for one thing, are a little ridiculous. I mean, they’re constantly screwing up.

Sounds like you use them, though?

Well, sure, how else am I going to speak to my fiancé’s father in Ieper, Belgium, when he hasn’t bothered to learn English?

Of course. So what else?

You said that cancer was reduced, but that’s actually quite understated. Bioengineered treatments, particularly antiangiogenesis drugs that prevent tumors from growing the capillaries they need, have eliminated most forms of cancer as a major killer.[6]

Well, that’s just not a prediction I was willing to make. There have been so many false hopes with regard to cancer treatments, and so many promising approaches proving to be dead ends, that I just wasn’t willing to make that call. Also, there just wasn’t enough evidence when I wrote the book in 1998 to make that dramatic a prediction.

Not that you shied away from dramatic predictions.

The predictions I made were fairly conservative, actually, and were based on technologies and trends I could touch and feel. I was certainly aware of several promising approaches to bioengineered cancer treatments, but it was still kind of iffy, given the history of cancer research. Anyway, the book only touched tangentially on bioengineering, although it’s clearly an information-based technology.

Now with regard to sex—

Speaking of health problems…

Yes, well, you said that virtual partners were popular, but I just don’t see that.

It might just be the circle you move in.

I have a very small circle—mostly I’ve been trying to get Ben to focus on our wedding.

Yes, tell me about him.

He’s very romantic. He actually sends me letters on paper!

That is romantic. So, how was the phone call I interrupted?

I tried on this new nightgown he sent me. I thought he’d appreciate it, but he was being a little annoying.

I assume you’re going to finish that thought.

Well, he wanted me to kind of let these straps slip, maybe just a little. But I’m kind of shy on the phone. I don’t really go in for video phone sex, not like some friends I know.

Oh, so I did get that prediction right.

Anyway, I just told him to use the image transformers.

Transformers?

You know, he can undress me just at his end.

Oh yes, of course. The computer is altering your image in real time.

Exactly. You can change someone’s face, body, clothing, or surroundings into someone or something else entirely, and they don’t know you’re doing it.

Hmmm.

Anyway, I caught Ben undressing his old girlfriend when she called to congratulate him on our engagement. She had no idea, and he thought itwas harmless. I didn’t speak to him for a week.

Well, as long as it was just at his end.

Who knows what she was doing at her end.

That’s kind of her business, isn’t it? As long as they don’t know what the other is doing.

I’m not so sure they didn’t know. Anyway, people do spend a lot of time together up close but at a distance, if you know what I mean.

Using the displays?

We call them portals—you can look through them, but you can’t touch.

I see, still no interest in virtual sex?

Not personally. I mean, it’s pretty pathetic. But I did have to write the copy for a brochure about a sensual virtual reality environment. Being low on the totem pole, I really can’t pick my assignments.

Did you try the product?

I didn’t exactly try it. I just observed. I would say they put more effort into the virtual girls than the guys.

How’d your campaign make out?

The product bombed. I mean, the market’s just so cluttered.

You can’t win them all.

No, but one of your predictions did work out quite well. I took your advice about that company north of the Mason-Dixon line. And, hey, I’m not complaining.

I’ll bet a lot of stocks are up.

Yes, the boats keep getting higher.

Okay, what else?

You’re right about the disabled. My office mate is deaf, and it’s not an issue at all. There’s nothing a blind or deaf person can’t do today.

That was really true back in 1999.

I think the difference now is that the public understands it. It’s just a lot more obvious with today’s technology. But that understanding is important.

Sure, without the technology, there’s just a lot of misconception and prejudice.

True enough. I think I’m going to have to get going, I can see Ben’s face on my call line.

He looks like a St. Bernard.

Oh, I left my image transformers on. Here, I’ll let you see what he really looks like.

Hey, good-looking guy. Well, good luck. You do seem to have changed.

I should hope so.

I mean I think our relationship has changed.

Well, I’m ten years older.

And it seems that I’m asking you most of the questions.

I guess I’m the expert now. I can just tell you what I see. But how come you’re still stuck in 1999?

I’m afraid I just can’t leave quite yet. I have to get this book out, for one thing.

I do have one confusion. How is that you can talk to me from 1999 when I’m here in the year 2009? What kind of technology is that?

Oh, that’s a very old technology. It’s called poetic license.

1 A consortium of eighteen manufacturers of cellular telephones and other portable electronic devices is developing a technology called Bluetooth, which provides wireless communications within a radius of about ten meters, at a data rate of 700 to 900 kilobits per second. Bluetooth is expected to be introduced in late 1999 and will initially have a cost of about $20 per unit. This cost is expected to decline rapidly after introduction. Bluetooth will allow personal communications and electronics devices to communicate with one another.

2 Technology such as Bluetooth (see note 1) will allow computer components such as computing units, keyboards, pointing devices, printers, etc. to communicate with one another without the use of cables.

3 Microvision of Seattle has a product called a Virtual Retina Display (VRD) that projects images directly onto the user’s retinas while allowing the user to see the normal environment. The Microvision VRD is currently expensive and is sold primarily to the military for use by pilots. Microvision’s CEO Richard Rutkowski projects a consumer version built on a single chip before the year 2000.

4 Projecting from the speed of personal computers, a 1998 personal computer can perform about 150 million instructions per second for about $1,000. By doubling every twelve months, we get a projection of 150 million multiplied by 211 (2,048) = 300 billion instructions per second in 2009. Instructions are less powerful than calculations, so calculations per second will be around 100 billion. However, projecting from the speed of neural computers, a 1997 neural computer provided about 2 billion neural connection calculations per second for around $2,000, which is 1 billion calculations per $1,000. By doubling every 12 months, we get a projection of 1 billion times 212 (4,096) = 4 trillion calculations per second in 2009. By 2009, computers will routinely combine both types of computations, so if even 25 percent of the computations are of the neural connection calculation type, the estimate of 1 trillion calculations per second for $1,000 of computing in 2009 is reasonable.

5 The most powerful supercomputers are twenty thousand times more powerful than a $1,000 personal computer. With $1,000 personal computers providing about 1 trillion calculations per second (particularly of the neural-connection type of calculation) in 2009, the more powerful supercomputers will provide about 20 million billion calculations per second, which is about equal to the estimated processing power of the human brain.

6 As of this writing, there has been much publicity surrounding the work of Dr. Judah Folkman of Children’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and the effects of angiogenesis inhibitors. In particular, the combination of Endostatin and Angiostatin, bioengineered drugs that inhibit the reproduction of capillaries, has been remarkably effective in mice. Although there has been a lot of commentary pointing out that drugs that work in mice often do not work in humans, the degree to which this drug combination worked in these laboratory animals was remarkable. Drugs that work this well in mice often do work in humans.

See HOPE IN THE LAB: A Special Report. A Cautious Awe Greets Drugs That Eradicate Tumors in Mice, New York Times, May 3, 1998.

— Ray Kurzweil (1999), The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence, Chapter 9, 2009, pp. 189-201. New York: Penguin.

Oh, well, whatever.

I think what’s interesting about this is not so much what Kurzweil predicts which hasn’t come to pass, but rather the number of things he failed to predict which have come to pass—and why the things he predicts coming to pass haven’t come to pass. Sometimes it’s because Kurzweil is too optimistic about technologies that never materialized, or which are still in their incipient stages at best. But a lot of the time, it’s just that people found they have better things to do with their limited time and resources. So it turns out that a lot of people do book travel reservations online now, but nobody books it by talking with some animated virtual customer service agent. Not because it would be impossible for clever folks to program that sort of thing, if they’d spent the last 10 years working on it. But rather, even if they did, who would want to waste time on that kind of goofy shit, when you can just get the tickets through Kayak? Similarly, I’m sure that if folks had spent the last 10 years working on virtual reality games, or on establishing fancy new paperless Information Superhighway channels for great big established media companies to push their DRMed-up chosen publications, you probably would have seen something like what Kurzweil predicts. But instead of that, we have people who put their time into developing IndyMedia, Craigslist, blogging software, and Flickr, MySpace, and so on—tools which, technically speaking, are mostly dead-simple HTML over HTTP. The real awesomeness of the future — so far, at least — turns out to have not nearly so much to do with technical fireworks and the kinds of techno-conveniences that brute-force computational power can achieve, but rather with the new lifestyles, new patterns of autonomy, and the new forms of social relationships that relatively simple but increasingly pervasive technologies, have helped facilitate. And which are going to continue to grow, and transform, and, ultimately, are going to turn this old world upside-down and inside-out.

Have an awesome new decade, y’all.