Here’s another account from the mainstream New York press — this time, from the New York Times — on the New York “Committee of Safety” and on the police attack on labor protesters in Tompkins Square. Like the previously posted stories from the Herald, the paper treated the protest as a project of “The Communists,” in the midst of the United States’ first great Red Scare. Also notable here is an early press appearance for Justus Schwab, here arrested with a red flag around his waist, later known and beloved by the Anarchist community in New York City as the owner of a “Beer-Hole” on First Street, which provided a meeting-place for radicals, political refugees, writers and artists that Emma Goldman remembered as “the most famous radical center in New York.”

DEFEAT OF THE COMMUNISTS

THE MASS-MEETING AND PARADE BROKEN UP.

ENCOUNTER BETWEEN THE MOB AND THE POLICE–ARREST OF RIOTERS.

The Police Commissioners wisely refused permission to the Communists to parade yesterday. There would have been no objection to an honest working men’s parade, but the great majority of the working men, through their acknowledged representatives, disclaimed all connection with the projection display, and it was therefore considered unadvisable to permit a few malcontents to disturb the peace of the City. The events of yesterday sufficiently proved the wisdom of the prohibition, and the bad spirit that unfortunately is rife among the more worthless sections of the community. In spite of the refusal it was stated early in the day that the meeting would be held, and by 10 o’clock Tompkins square and vicinity were occupied by perhaps 3,000 persons of the lowest class, most of whom, however, were probably there out of idle curiosity. At 10:15 the Police, under Commissioner Duryee and Capts. Walsh, Murphy, Tynan, and Allaire, with platoons from their respective precincts, the Seventeenth, Eleveneth, Eighteenth, and Twenty-first, marched into and cleared the square, while a mounted squad scoured the streets in the vicinity. Capt. Walsh, with Sergts. Cass and Berghold and twenty-two men, made for the largest crowd, assembled round a banner inscribed The Tenth Ward Working Men’s Organization,

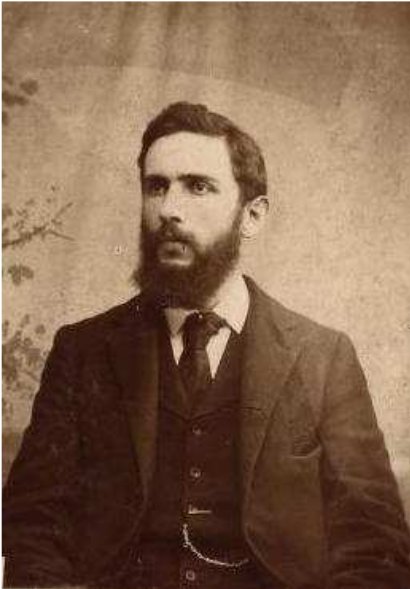

and here there was a fray, in which Sergt. Berghold had his head broken, and his assailants fared no better. They told their stories afterward at the Seventeenth Precinct Station-house, corner of Fifth street and Second avenue, where they were conveyed, and at which thenceforward the interest centered. Christian Meyer, who struck the Sergeant, confessed his misdeeds with much naivete, as he was sitting with head bandaged and a broken wrist in a sling in the officers’ quarters. He said he was a painter by trade, belonging to an association with 3,000 members; that there were about 100 of them only present; that every one was armed in some way, his own weapon being a claw-hammer, with a thong to put his hand through; and that they had orders not to fight unless they were attacked. The Sergeant pushed him, so he obeyed orders and hit the Sergeant. Justus Schwab, another captive, who wore a red flag around his waist, said his father had served four years’ imprisonment for riot at Frankfort, Germany: that he had been four years and eight months in the country, and fourteen weeks out of work. He thought every man should defend the State, and that the State should provide for every man. He thought the working men would triumph, and commenced to sing the Marseillaise, a performance which was checked. On Hofflicher, another leader, was found a somewhat elaborate Communistic badge. The vicinity of the station-house for several blocks was thronged until quite late in the afternoon, and in the Bowery as far down as Canal street, knots of men were gathered on the corners as late as 2 o’clock, waiting for the procession. In the vicinity of the Seventeenth Precinct Station-house the task of dispersing the multitude kept the officers well employed. There were incessant skirmishes in which clubs were judiciously applied with seasonable but not excessive severity, and prisoners were continually being brought in. The scrambles of the mob as the officers advanced were not unamusing; in fact, it seemed as if they rather enjoyed the exercise. The housetops and windows for blocks were crowded with patient spectators.

At 3:45 P. M. the prisoners were marched to Essex Market Police Court, and arraigned before Justice Flammer, who held them in default of $1,000 bail each. The schools soon after filled the streets with children and a more respectable class of citizens appeared. The trouble was evidently over. It was at no time beyond easy control. The forbearance and good humor of the Police were admirable. There were unpleasant incidents, however, which showed plainly that a neglected spark might have been fanned into a dangerous flame amid the unamiable passions abroad. Alderman Kehr, about noon, was passing through Fourth street, when he was recognized, and as the cry was raised, Here’s an Alderman–go for him!

he jumped on an Avenue A car, but was again recognized, the car boarded, and he had to jump off again and run for his life. Police Commissioners Charlick and Gardner visited the Seventeenth Precinct in a coupé at 4:30 P. M.

THE COMMITTEE OF SAFETY

BEFORE THE MAYOR

The Mayor arrived at his office at noon. When he had taken his seat, his Secretary handed him a card containing the request, Mr. Leander Thompson would like to have an interview with his Honor.

The Mayor recognized the name as that of a member of the Working Men’s Committee of Safety,

who had previously called upon him as a representative of the labor movement, and at whose request he had promised to address the laborers at Union square. The Mayor told his Secretary to admit Mr. Thompson, and the latter, accompanied by Messrs. John McMichael, George Buck, John Halbert, and Luceen Saniel, entered the office. Gen. Duryee, the Police Commissioner, was in an adjoining chamber, and, the moment Thompson entered, the Mayor called him to his side.

Well, gentlemen,

said the Mayor, I am ready to hear what you have to say.

Mr. Thompson, in response, said the deputation represented the Committee of Safety, and they had called to escort his Honor to Tompkins square where, they hoped, he would address the people.

Mayor Havemeyer–I have heard what occurred this morning, and I do not desire to address crazy or excited people, who might be anxious to send brickbats flying.

Mr. Thompson–The people would like to hear your views. We will take you in a carriage. The working men are a peaceable and orderly class. They made an attempt to meet and express their views and were forcibly ejected by the Police, who clubbed and trampled upon them.

Mr. McMichael here stepped forward and said, Mr. Mayor, I hope you will come with us. We promised the people that you would speak to them, and they will be much disappointed if you do not. The meeting this morning was intended to be peaceable and orderly, but the Police interfered and clubbed every one they met. there were 20,000 persons in the square and its vicinity, and they were driven back without cause. I believe that it is absolutely necessary for you to come up and speak to the working men. They are very much excited about the treatment they have received from the Police, and consequences which we would wish to avert may follow if they are not spoken to.

Gen. Duryee interposed here. He said that all law-abiding citizens would act peaceably, and that he did not believe there would be any further trouble. But,

resumed Mr. McMichael, the Police treated the meeting most mercilessly. Without a moment’s warning they clubbed them off the ground.

Gen. [sic]Duryea[/sic], (warmly)–No, Sir; the Police did not act until a man came forward and struck a Sergeant on the head with a heavy hammer, which he had rigged

so completely that it was taken from him with difficulty. Then an attack was made upon a Captain, so that it was time to disperse the crowd.

Mr. Thompson–The Park Commissioners gave us a permit to meet in Tompkins square, and they rescinded it last night, so that we had no time to tell the people to keep away.

Mr. McMichael–The meeting was intended to be peaceable: we promised the people that you would address them, and it is necessary for something to be done to allay the feeling that exists.

Mayor Havemeyer–I would have addressed the working men to-day if they carried out the programme they submitted to me. They agreed to march from Tompkins to Union square, and I told you that I would speak to them before they were dismissed at the latter place. Instead of doing what they agreed to do, they held a mass-meeting at Tompkins square without authority.

One of the deputation here remarked that the programme was changed on the previous night, so as to enable the working men to hear addresses.

Mr. Thompson–Our original intention was to march down to the City Hall, so as to see the authorities about getting employment.

Commissioner Duryee–But the Police Commissioners had to forbid that, because a large procession would interfere with business in the crowded thoroughfares below Canal street.

Mr. Halbert–This is a diversion. We desire to know if your Honor will come with us to address the working men.

Mayor Havemeyer–I must leave the matter to Commissioner Duryee.

Commissioner Duryee–I think it would be unadvisable for you to go. Let these gentlemen come again, and I am sure that all that can be done for the unemployed will be done by the City.

Mr. McMichael–We have been denounced by the press without cause. We have been called Communists, and our objects have been misrepresented. All we want is work.

Mayor Havemeyer–Well, there is one difficulty in the way. The market in this City is glutted with labor, and men will not work unless they can get the price they ask. I believe that there is work enough for everybody, but not at the wages demanded. (To Mr. McMichael.) What is your business?

Mr. McMichael–I am a painter.

Mayor Havemeyer–Well, many a man who can’t, at the present rates, get his house painted for less than $300 would willingly give $200 to have it done. But, as he has got money, he can afford to wait until he can have the painting done at the sum he wishes to pay for it.

Mr. McMichael–It is necessary to get good prices to live now.

Mr. Thompson–The working men can’t demand employment from private parties, so they must demand it from the Government.

Mayor Havemeyer–It is not the purpose or object of the City Government to furnish work to the industrious poor. That system belongs to other countries, not to ours. We can’t tear down the City Hall so as to furnish work to the unemployed. We have to open streets and proceed with other works such as are rquired, and it takes time to authorize these according to law.

Mr. Thompson–But is it not the duty of the Government to furnish rations to starving men and their families?

Mayor Havemeyer–I agree with you that rations should be furnished to those who need them, and I am ready to advance a movement of that kind to the full extent of my power. The people of this City are too large-hearted to allow any person to suffer from starvation.

Mr. Thompson–Well, perhaps it’s better for your Honor not to come with us to-day; so we shall not urge you. But we must see the people, lest they should blame us for not bringing you to Tompkins square. Will you (turning to Commissioner Duryee) give us a letter to the other Commissioners, so that we may procure a pass to enter Tompkins square. If we don’t get a pass, we’ll get clubbed by the Police.

Commissioner Duryee–There is no necessity for a note. See Commissioner Smith. You can easily see him.

The deputation then left. Immediately after they had retired, the Mayor said: I am in favor of raising subscriptions from merchants and others, so as to alleviate any suffering that may exist among working men and their families. Money would be soon forthcoming for the purpose, and a hall could be hierd and a clerk engaged to serve out rations of all kinds to the hungry. Money could also be advanced to those who were unable to pay their rent.

THE RIOTERS IN COURT.

Essex Market Police Court was particularly lively yesterday afternoon when Capt. Walsh, of the Seventeenth Precinct, assisted by twenty-five patrolmen marched in the prisoners whom they had arrested for riotous conduct around Tompkins square. The would-be Communists looked dogged and obstinate, evidently thinking that they would be at once discharged. They were considerably disappointed, however, when it was made known to them that the full penalty of the law would be meted out to them. They all expected friends

would come forward and exert mysterious influence in their favor, but their expectations were all in vain. Some few of them, more impudent than others, said, Oh, the Judge dare not do anything to us; we are too powerful, and the people would tear down the prison.

After the ordinary business had been disposed of, Justice Flammer directed the prisoners in charge of Capt. Walsh to be brought before him. The rioters were then all marched up to the desk, and formal complaints were entered against every one of them, charging them with assault and battery and riotous conduct. Justice Flammer, after the complaints of the officers were taken, committed all the prisoners, in default of $1,000 bail each, to stand their trial. They were all taken into the prison, and when there were visited by a Times reporter. They appeared only to be realizing the fact that they had committed very serious offenses against the law, and many of them regretted that they had ever been drawn into joining the demonstration.