Now available: full text of “Slavery in Auburn, Alabama” (1907) posted by Charles Johnson 28 Aug 2016 3:28 pm

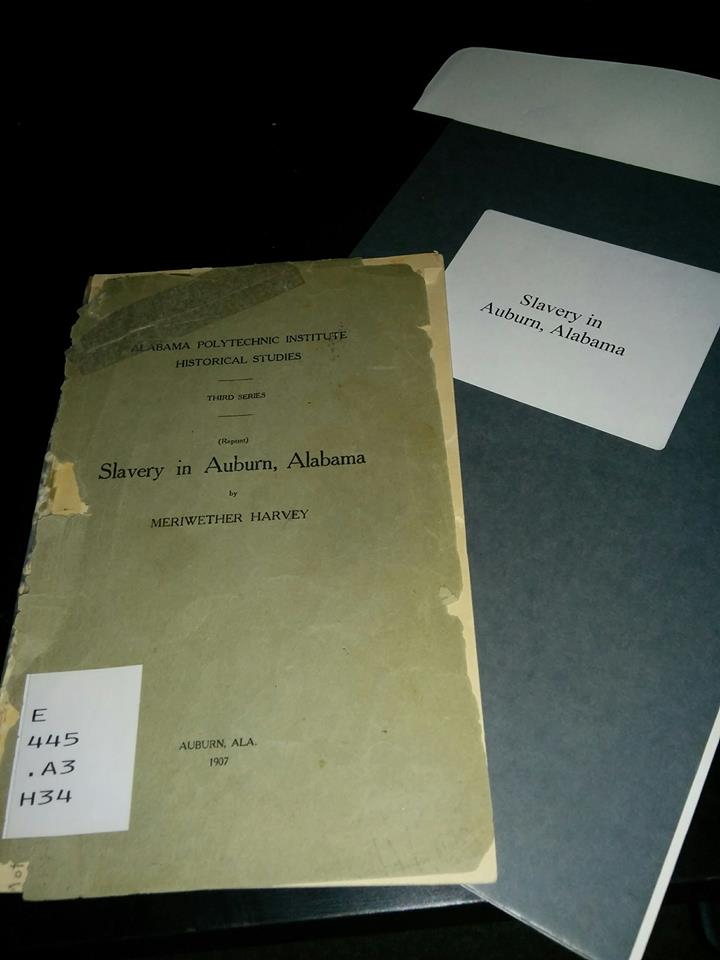

Now available on the Fair Use Repository website: I have just made available the full, transcribed text of Slavery in Auburn, Alabama, a small 18pp booklet from the Alabama Polytechnic Institute Historical Studies (published by Auburn University, then known as Alabama Polytechnic Institute) written by Meriwether Harvey.

I found the booklet on the shelves at the Auburn University RBD Library, an aging, decaying reprint booklet carefully tucked into a protective grey cover, and decided that this document of local history deserved preserving. So I have spent the past couple days reading and transcribing the text into digital form.

The booklet was written in 1907, and its viewpoint very emphatically reflects the views common among wealthy white families and former slaveholders (like the Harveys) in and around Auburn, Alabama, a small college town in what was then rural East Alabama. It is romanticized, although concerned enough with points of detail and description that that only causes a problem in some parts of the booklet. At times, the text is oblivious, or frankly racist. It makes some blanket claims about the local slave trade that are almost certainly self-serving lies told by the author’s sources. However, the booklet seems to have been based primarily on first-hand interviews with slaveholding white families and a few interviews with African-American residents who had been born under slavery, and whether intentionally or unintentionally provides fascinating points of detail, and anecdotes reflecting the reminiscences, the self-justifying fantasies, and also the anxieties of white slaveholders in East Alabama, as well as some of the range of experiences of slavery in east Alabama, and the operation of the slaves’ economy, despite its frustrating limitations. Some excerpts:

Slavery in Auburn, Alabama (1907)

By Meriwether Harvey

[…] Corn shucking was another great occasion in the negro’s life. The owner would have all his corn hauled up and thrown on the ground at the crib door in a big pile; then he would invite his neighbors’ negroes to come to his house on a certain night to a corn shucking. Only the men were invited; as they came they could be heard in the distance singing corn songs. I have tried to record some of these songs, but I find they were a jargon; they had no real words, only a tune. Some disinterested man would lay a long pole in the middle of the pile; then two negro men would choose sides, as is done today in spelling matches, and the two sides would enter into a contest to see which could first finish their side of the pile. The leader, dressed in a stove pipe hat and feather, walked up and down on the pile and gave out the corn song. The whole crowd answered him in the chorus. As they shucked, they would throw the corn into the barn in front of them and the shucks behind. When they had finished about half of the pile, corn whiskey was passed; thus they worked till eleven o’clock, when [13] they had a big plain supper. After eating the put the shucks in pens made for the purpose. By twelve they had finished, and then the frolic began. They danced about the great bonfire that had been burning all the time behind them, so that they might have sufficient light to shuck the corn, the lights and shadows making a strange and ghostly scene. After the supper the owner of the plantation, the giver of the corn shucking, or sometimes the overseer, was seized and carried about on the shoulders of some of the negroes. The other negroes followed, all singing at the top of their voices. About two or three o’clock in the morning they all went home.

[…] The treatment of slaves was generally good because the negro was property and was cared for as such. [sic] I have interviewed only one man who ever saw a slave unmercifully beaten. [sic] A great many negroes would run away; some of them were chronic runaways, and were so seemingly without any cause whatever. A few of these chronic runaways were chained at night. Certain people all through the country kept fox hounds for tracking runaway negroes, who would go off into the swamps and woods. It was often impossible to catch them in any way except with dogs. They were seldom bitten by the dogs when over taken; they would climb a tree if one was near at hand, but if they were caught on the ground, the dogs were so trained that they circled around the negroes, without going close to them. Negroes always aided a runaway by slipping to him something to eat. Mr. H. never had a negro to lie out more than three days, and never offered more than ten dollars as a reward for his return. Mr. B., with the aid of another man, caught a negro who had been in the woods seven years. He advertised the negro, and in due time returned him to his master. The slave turned out to be the most faithful of a large number of slaves. Mrs. D. says of her whole [15] number of slaves, which was between one hundred and fifty and two hundred, there was never a runaway; Mr. B. knows several such cases. Uncle West would run from the plantation up to Mr. F. R.’s residence whenever the overseer told him to do what he did not wish to do, or threatened to whip him. None of the negroes ever did any other kind of running away.

The overseers were men selected for their practical farming ability, and their business was to oversee the negroes and look after the farm and the planting. Sometimes an overseer was discharged, or brought to trial, when he mistreated a negro. One of Mr. W. H.’s overseers whipped two of his negroes, who hid in the swamp. Some of the other negroes came from the plantation to Auburn to tell their master. He decided the whipping unjust and paid the overseer up and let him go.

When an overseer was hired it was understood that he was to ride the country as a patrol; also the young white slave-owners of the neighborhood patrolled on certain nights. A negro was not allowed to leave his master’s plantation without a pass stating where he was going and when he was to return. This had to be signed, either by the overseer or the master. If the negro was caught away from home without a pass, he was whipped with a leather strap by these patrols. The usual punishment for being away from home without a pass was ten to twenty lashes, but in exceptional cases thirty-nine lashes might be given. These patrols went usually Saturday nights and Sunday afternoons and nights, but they also went out any night when they thought they might catch negroes roving about. They patrolled the roads, visited the plantations, and searched the cabins; if a negro was caught in a cabin away from home, he was taken off a good way from the negro quarters and whipped. Of course the whipping depended upon the offense, the mood of the patrol, and the negro whipped. Sometimes people who did not own negroes would catch a [16] negro without a pass and beat him badly, but the regular patrol did not do this.

The negroes were punished as a rule, by whipping; the whip was a leather strap so that it would not cut the skin. The foreman was the boss and did the whipping, but the owner, or overseer, was there to witness it. On some plantations the overseer did the whipping, but the master was usually present. Negroes were not whipped for small offenses; a foreman would sometimes dislike a certain negro and would beat that one unmercifully. As a rule, the overseer was more kind and merciful than the foreman. If there was a large number of hands, the foreman spent his whole time bossing; if the number was small, he would work awhile and then boss awhile. He lorded it over the other negroes. The worst whipping was often done by the negro parents.

[…] Slavery was not without its dark side. There were near Auburn several instances of cruel treatment to slaves. In one case they were not properly fed, in another, they were not sufficiently clothed. How far this was due to the lack of means of the masters is now hard to determine. In some cases they seem to have been overworked. In one or two they were treated roughly and punished severely. In one case a slave stabbed his master, but did not kill him. The slave was tried and hanged. Public opinion disapproved of cruelty on the part of masters. One man was indicted three times for ill treatment of his slaves, especially for failing to supply them with sufficient food and clothing. He was fined each time.

[18]There were some old negroes who did as they pleased and went where they pleased. These negroes were too old and infirm to be of any value. Mr. H. had four or five such, two of whom were blind women. They made money by making baskets and selling chickens and eggs. These negroes were not what were called free negroes. Uncle Burl Dillard was in reality a free negro, but he nominally belonged to the Dillards. He made ginger bread and persimmon beer, which he sold. He also had a wagon and mule, and went through the country buying old rags which he took to Columbus and there sold. His wife, Aunt Kitty Dillard, was a slave.

The negroes had the greatest contempt for poor white folks, that is people who owned no negroes. Every one speaks of their faithfulness. They would divide anything they had with their masters and would steal from their neighbor rather than their master. Only cribs and smoke houses were locked. They thought their folks the greatest in the world, and what belonged to the master was always spoken of as theirs. They were respectful to every one except poor white folks. Mr. R.’s negroes came from South Carolina and would not associate with other negroes because they thought South Carolina negroes far superior to any of the negroes in Auburn. In 1847 Aus Harvey went to Mexico with his master. When they left, the mother of Mr. Harvey made Aus promise to bring her son back if he should die. Mr. Harvey died with yellow fever, and true to his promise, Aus brought the body home. He paid his own fare and that of the corpse by cooking and doing various things. He told parties that the corpse was a piece of furniture he was bringing to Alabama. Finally, he got the body as far as Montgomery; then the family sent for it. There were many examples of faithfulness, too numerous to be told.

–Meriwether Harvey, Slavery in Auburn, Alabama (1907)

This is from

This is from